From the beginning of his career, Lucero challenged the perceived limitations

of his chosen material—clay. His definition of "fine art" was not limited

to paint and canvas, stone, metal, or wood. Instead, as is the case in

many non-Anglo cultures, for Lucero the concept of fine art equally defines

archeology, including ceramic-based vessels and figural forms. While working

in the Bay Area, Lucero realized, "I don’t have to weld or chisel wood

or carve stone to be able to make sculpture…there were all these wonderful

alternatives…. [Using clay I could] make something that was [as] justified

or legitimate as anyone else….yet have my own identify felt through the

work." Once Lucero committed to working primarily in clay, he was determined

to grant it the primacy traditionally given oil paint or marble. This implicit

faithfulness to the integrity of his material permeates all his work.

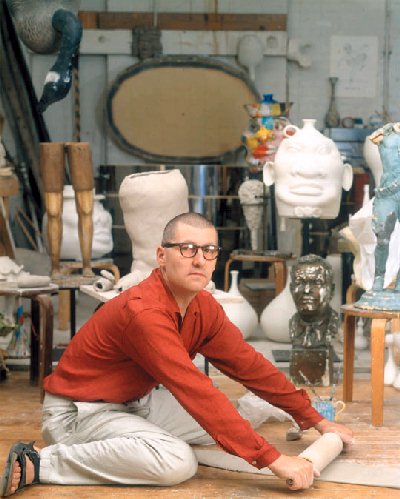

Beginning with the simplest techniques of hand-building, pinching, and

rolling out forms, Lucero created an enduring affinity between himself

and his chosen material that has lasted for over two decades. But Lucero’s

maverick vision presented the artist with challenges unlike any he imagined.

Lucero was immersed in figuration at a time when Minimalism, performance,

and earth art were among the dominant and critically accepted art forms.

An ardent admirer of global culture, he often incorporates specific stylistic

references to one culture or another into his work, creating complex, hybrid

forms. Throughout his career, he was discouraged by many in the art world

from describing those interests in his work. But he persevered, and the

stunning results of this career-long odyssey are a provocative and enduring

body of sculpture that illustrates the fluid, dynamic character of global

culture.

The exhibit Michael Lucero: Sculpture 1976–1995, now at the Carnegie Museum of Art, presents two decades of the artist’s glazed ceramic, bronze, and mixed media sculptures, including such series as the Shard Figures, Dreamers, Pre-Columbus, New World, and Reclamation. While at first glance his work appears to be a vigorous example of contemporary ceramic sculpture, with a background in 1960s California art and a foreground in New York eclecticism, in fact his figurative forms borrow liberally and wittily from the history of art of various cultures, including pre-Columbian and Native American; the European avant-garde; African-based forms; and George Ohr ceramics, as well as the vernacular and mass media. Since the 1970s Lucero has consciously moved backwards and sideways through the history of art. His most recent work incorporates found objects of popular art and culture.

The imagery that slides in and out of the complex glazes of this master of the ceramic medium is art about art, art about place, art about self. The consistent strength of the work comes from a fusion of ceramic tradition with sculptural innovation, and from a combination of extraordinarily fine technique, keen wide-ranging intelligence, and the resonance brought to bear by past associations, cultures, and use.

Taken as a whole, Lucero’s artworks contain three core elements: an ecumenical borrowing from the history of art of various cultures, a persistent metaphorical and physical movement between interior and exterior structures and spaces, and a faithfulness to the ceramic medium. The artist’s creative reworking of multicultural forms and his exploration of such contrasting ideas as beauty and the grotesque, culture and nature, the sacred and the profane, ritual and accidental, and purity and contamination offer an authentic model of cultural pluralism. Technically, visually, and conceptually, Lucero’s work offers immediate access to alternate notions of originality and cultural relativity. The visual and formal diversity of his works is a metaphor for contemporary life and collective existence in which there is not one predominant culture, but many voices existing simultaneously.

Courtesy of The Mint Museum of Art.

Copyright 1998 Carnegie Magazine All

rights reserved. Email: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |