For nine months the Atlantic puffins are at sea, flying over the Atlantic Ocean and sparsely inhabited coasts and islands from Labrador to New England, and from Greenland to Norway and Brittany. Then for three months in the summer they settle down, nesting on rocky shores where they raise their young in underground burrows. The long-lived puffin survives for decades, and is faithful to one mate for many years. Each breeding season they produce one chick. Over time, colonies develop as the birds return year after year to a favorite nesting site and burrow in coastal areas where they can feed their young.

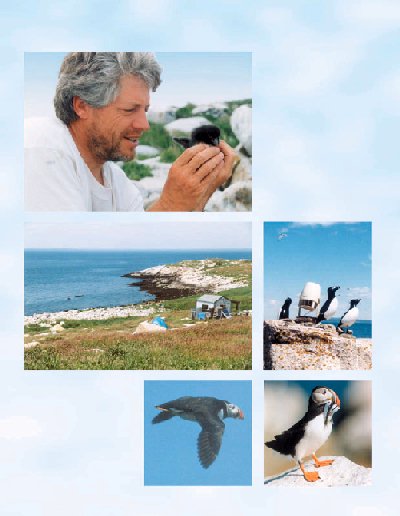

The puffin has special characteristics that humans find easy to enjoy—a

rolling, slightly comic hop and walk, a beautifully colored and dramatic

head and beak, and a quizzical head-cocking stare when they inspect something

unknown. "People just can’t resist puffins," says Ken Parkes,

curator emeritus of Birds at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, adding,

" They are probably the most photographed bird in existence."

Bennington volunteered, and for three weeks in the summer of 1997 spent a largely solitary time on Seal Island, 21 miles off the coast of Rockland, Maine. The task of the volunteers on the island was to observe and document the hoped-for return of native seabirds on different parts of this island, which was once the largest Atlantic puffin colony in the Gulf of Maine. Chicks were banded, making it possible for future volunteers to document the return of puffins—which typically might not happen for several years.

The chance to get involved in something entirely different from his work as a science center director was one reason Bennington volunteered. But equally important was what he describes as the opportunity for "the renewal of soul" on the solitude of a wind-swept Atlantic island. As he wrote later: "The calm murmer of an exhausted sea after a wild night of crashing waves and wind-driven rain, the spectacular night lightning illuminating the island from end to end, the rhythm of the tides, the scarlet brushstrokes of dusk, all restore one’s sense of place in a natural world of detail, drama and beauty."

Many volunteers in the Seabird Restoration Program along the Maine coast are graduate students preparing for careers in wildlife management, to whom living in the wild is part of their professional experience. A good many volunteers are established professionals in other fields, drawn by their commitment to environmental restoration, and the chance to experience life in a natural and lonely frontier of the modern world. In all some 30 volunteers joined the Maine coast staff for Project Puffin from May until August, 1997. The entire project included six different islands, and during the period volunteers typically took turns of several weeks sharing the responsibilities.

This remote grass and granite island offers a habitat that many species of seabirds love. Its boulder fields and ledges attract puffins, razorbills, and black guillemots. The grass and ledge areas are favored by terns, the raspberry and grass thickets appeal to eiders, and the soft peat and glacial tills are ideal for burrowing by Leach’s storm petrels. The rich fishing grounds offshore attract populations of harbor and gray seals—which led to the name of the island.

For 200 years fishermen used Seal Island as a summer campsite while fishing for herring, groundfish and lobsters. People harvested the seabirds for meat, and collected eggs and feathers. Seal Island, only 100 acres and treeless, was a bombing and shelling target from the end of World War II until 1952. But in 1972 the island became part of a chain of national wildlife refuges along the coast of Maine. Today it is owned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and is part of the Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. It is managed by the National Audubon Society (NAS).

Once a habitat is disturbed by man, animals do not automatically return. A typical scenario for returning bird populations along the Maine islands sees large numbers of gulls crowding out smaller species, such as terns. In fact predatory gulls can so completely eliminate competition from other species trying to recolonize an area, that the Audubon Society manages specific "no gull" zones.

A volunteer’s duties typically included daily bird counts, three-hour observation stints behind a "bird-blind" observation structure, and censusing. Day after day Seddon monitored the puffins returning to a favorite rocky area. In time he came to identify about 20 individuals. Their courtship and mating occurred underground, out of sight, and the location of eggs and chicks had to be verified by constant observation. The puffins fished with the changing tides, and took turns feeding their young chicks. With the use of a "spotting scope" an observer can see and record the numbers on a previously banded adult bird. As a chick nears fledging, the volunteer goes to the site and gives it an identifying band on its leg.

"Puffins are wonderful to watch," says Seddon. With so much time for continuous observation, a bird watcher recognizes the subtle clues and behavior patterns that differentiate individual birds. They were not only beautiful, but easy to imagine with comical human traits. "Their walk, their slightly quizzical look," he says, "made it impossible not to describe their behavior in human terms."

The brightly ornamental beaks of puffins are an attraction during the mating season. With these beaks and the unusual feature of internal spikes with which they can hold prey, they have the extraordinary capacity to catch not one but several fish in a row as they hunt for food beneath the waters. Puffins return to their nests with several fish at a time to feed a fast-growing chick. In the fall puffins shed the colorful outer plates that have grown around their beaks during the mating season, and display their otherwise smaller bills. They are like deer which shed their antlers annually, only to grow them again next year.

For Seddon Bennington, Project Puffin was a second experience in monitoring wild seabirds. Many years before, in 1969, he had banded albatrosses in the Sub-Antarctic. As a native of new Zealand, he was early fascinated by the patterns of migrating wildlife. And he has traveled to remote areas of Indonesia and other parts of the world. Project Puffin was therefore one more environmental adventure for him to pursue.

But his experience on Seal Island is also a reminder that worthy environmental causes are often easily found and pursued, if people have an interest in expressing their personal sense of stewardship of the natural world. For further information on the Seabird Restoration Program, of if you want to "Adopt-A Puffin," write the National Audubon Society, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850.

R. Jay Gangewere is editor of Carnegie Magazine.

Copyright 1998 Carnegie Magazine All

rights reserved. Email: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |