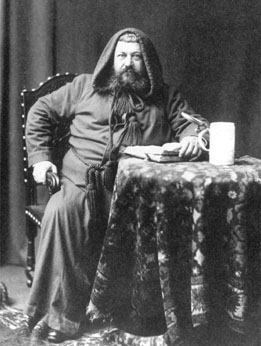

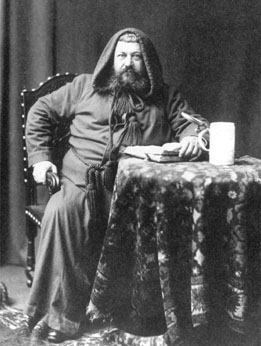

H. H. Richardson was a party animal. The renowned architect of Boston’s

Trinity Church and Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County Jail and Courthouse equally

enjoyed the pleasures of art and appetite. As a handsome, wealthy, charming

and athletic youth, Richardson’s student years at Harvard were noted for

their celebrations—not scholarship. Close college friendships grew into

lifelong alliances. As James F. O’Gorman notes in Living Architecture:

A Biography of

H. H. Richardson, "without his Harvard social connections he would

have had no architectural practice, or at least a very different one....Appreciative

friends equal potential clients."

Talent and personality: few architects of his or any other generation have matched Richardson’s stunning capacity for work and play. Infectious charisma and unprecedented originality led him to fully enjoy his tragically short life. If great architecture were simply a by-product of joie de vivre, then this entertaining new biography would be a fine instructional manual.

As O’Gorman traces Richardson’s social and architectural development, he also explores the often-neglected significance of pivotal patrons in the formation of great buildings. For instance, we are introduced to the "shining eyes and resonant voice" of Reverend Philips Brooks. His friendship with Richardson blossomed to produce Boston’s Trinity Church, a fresh and un-derivative sanctuary for rapidly maturing American culture. It is a bracing tale and well told. The year was 1871, and Richardson was only 33 years old.

In addition to loyal and supportive clients, Richardson also attracted talented teammates. He was an acutely perceptive critic who seldom drew, so he nurtured the skills of fine draftsmen and artisans. His studio boasted many well-known talents including the young architects Charles McKim and Stanford White, sculptor Augustus Saint Gaudens, and designer William Morris. Even muralist Edward Burne-Jones worked for Richardson. Cervin Robinson’s excellent, intensely colorful new photographs included here help to communicate the grace and solidity of Richardson’s efforts. Orthographic drawings—plans, sections, elevations—are conspicuously absent.

Legend has Richardson say, "If they honor me for the pygmy things I have already done, what will they say when they see Pittsburgh finished?" Sadly, Richardson would not live to find out. At the age of 48, Richardson was dead, in part a victim of his many indulgences. His last—and to many his finest—creation was Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County Jail and Courthouse. Richardson himself apparently saw it as his crowning achievement. But in the context of O’Gorman’s otherwise engaging exploration of patronage and persona, it is given short shrift. Who guided the competition process which resulted in Richardson’s selection? Who shepherded the design to ensure its power? We search O’Gorman’s text in vain for answers. Given the author’s compelling and otherwise well-developed theme of friendships and the resulting commissions, it leaves the reader with some unanswered questions. n

Paul Rosenblatt is an architect with Damianos + Anthony, Pittsburgh.

Copyright 1998 Carnegie Magazine

All rights reserved. Email: carnegiemag@carnegiemuseums.org

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |