|

Because Judaic objects relate to religious ceremonies, a basic consistency of ideas can be seen in the various types of Judaica. A Hanukkah lamp, for instance, has a recognizable form in the use of eight receptacles (either for oil or candles)-one for each day of the holiday, plus one called a shamash or "servant," which is used to ignite the others.

Although ritual use governs Judaic design, the ethnic diversity of Jewish communities worldwide produces many national and regional styles. Spice boxes, called hadassim (used in the Havdalah ceremony at the conclusion of Sabbath), are typical objects subject to regional interpretation. Those boxes made in Eastern Europe are reminiscent of the fortification towers that still stand in such cities as Prague. Decorative flags, shingles, and domes often top these hadassim. Indeed, a preference for historical styles, often derived from baroque and rococo models, influences the design of traditional Judaica.

Spices in the ceremony symbolize the spiritual riches of Sabbath, and

are blessed to ensure "that the new week should be fragrant in deeds,"

says Louis Jacobs in The Book of Jewish Belief (1984). The ritual of Havdalah

(the Hebrew word means "separation, division") celebrates separation from

Sabbath and distinguishes the holy Sabbath from the secular workweek. The

blessing is made over wine, candles and spices.

|

The ritualistic rules are basic to the contemporary designs of artists who create Judaica, but the 20th century has developed its own creative traditions. For example, the artist and teacher Ludwig Yehuda Wolpert (1900-1981) advocated contemporary design and promoted the production of Judaica in non-historic styles. A former professor of metalwork at the New Bezalel School for Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem, Wolpert came from Israel in 1956 to direct the Tobe Pascher Workshop at the Jewish Museum in New York, and his emphasis on artistic freedom and innovation can be seen in the work of his many former students.

Contemporary Judaica is made by both Jewish and non-Jewish artists, but all share a deep personal respect for the process of making spiritual objects for ritual use. This attitude was clearly fundamental to the four whom I interviewed about their craftsmanship: Robyn Nichols, Kurt Matzdorf, Sue Amendolara, and Harold Rabinowitz.

Robyn Nichols, a silversmith from Kansas City, produces a wide range

of Jewish ceremonial objects in silver, including alms boxes, Sabbath candlesticks,

and Havdalah sets. Nichols is not Jewish, but she studies Judaism to ensure

her designs have Jewish significance and also adhere to Jewish law. She

consults rabbis to receive clarification and answers to her questions,

and to ensure that her use of the Hebrew language is correct. She admires

Hebrew lettering and incorporates it regularly into her work. Stories from

the Torah, the Jewish Bible, and traditional Jewish symbolism also influence

her work. While keeping the function of the object integral to her final

design, Nichols enjoys interpreting each Judaic object in her personal

style. When she speaks about producing Judaica, she confesses that she

gets goose bumps because the subject can be so moving. Knowing that her

objects are cherished and are passed on within families inspires her to

continue making Judaica.

|

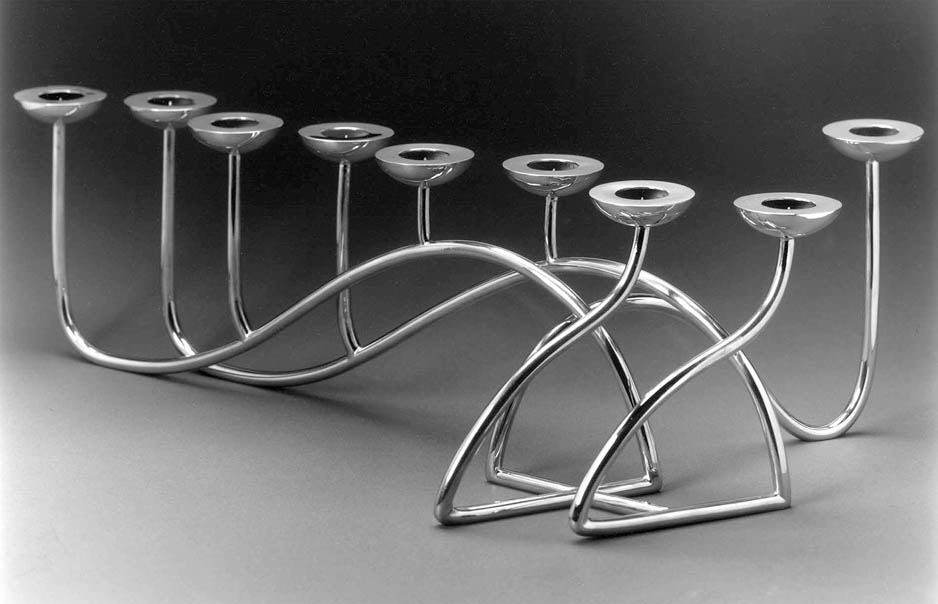

Kurt Matzdorf spends half of his time creating Judaica. The rest of his work consists of secular objects and jewelry. Matzdorf, a silversmith from New Paltz, New York, and professor emeritus of gold and silversmithing at State University of New York, has been working silver for 43 years. He enjoys working in a contemporary style, making objects that are of "today, but yet are timeless." He believes that since we live in the present, his mission is to interpret Judaica for contemporary people.

Matzdorf sees the history of art and sculpture from antiquity to present shaping his work and avoids "faddish styles." Matzdorf began his artistic career as a sculptor and says he evolved into a silversmith. His roots as a sculptor are evident in the Tree of Life motif on his Kiddush Cup. Currently working on doors for an ark-the permanent storage place for the Torah-for the Congregation of Beth Jacobs in Kingston, New York, he will include on the doors decorative symbols alluding to the Twelve Tribes of Israel. He sees his work in precious metal as "celebrating visually our history."

Sue Amendolara, silversmith and associate professor at Edinboro University

of Pennsylvania, submitted her work to this exhibition because the long

tradition of Judaica engages her creativity. Amendolara is noted for her

scent bottles, and she discovered that a spice box provided a natural transition

from secular to spiritual work. Although Palmetto Spice Box was her first

attempt at executing a "spiritual work," she believes that a strong relationship

exists between the silversmith and the ritual object. She has been asked

to make another Palmetto Spice Box and plans to participate in future Judaica

exhibitions.

|

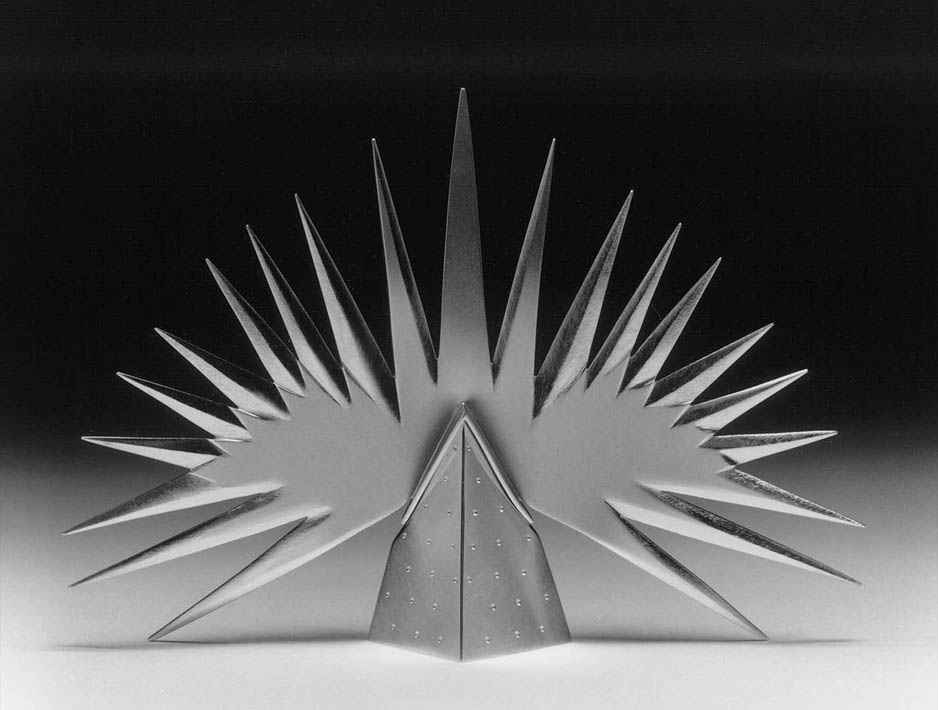

A maker of all types of Judaica for 37 years, Harold Rabinowitz works in Malvern, New York. He began making jewelry as a child. In 1979, he became a Fellow at the Tobe Pascher Workshop, and under the tutelage of Ludwig Wolpert began to make Judaica and other types of objects in a contemporary idiom. Working directly with Wolpert gave him a solid foundation, and he recalls the moment 17 years ago when his work took on its own character, becoming "more Rabinowitz." He sees his metalwork as sculpture that has a ritual function.

Rabinowitz's Torah Crown was originally made for the exhibition Jerusalem 3000, which celebrated the anniversary of the holy city. Because Jerusalem is considered the spiritual residence of God, a Torah crown had special meaning. Rabinowitz believes "Judaica throughout history is a reflection of its time."

Contemporary Judaica embraces the spirit of today's Judaism as a living religion. Each of the objects in Artisans in Silver: Judaica Today expresses this idea in bold contemporary style, yet each also demonstrates the ancient spirit of hiddur mitzvah: the "observance in beauty" of ritual ceremony.

Elisabeth R. Agro is curatorial assistant of Decorative Arts, Carnegie

Museum of Art.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |