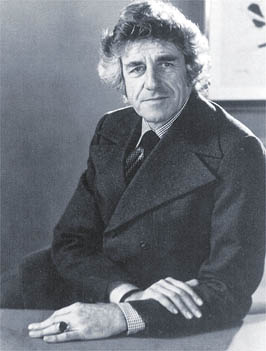

Less Was More for

A. James Speyer Less Was More for

A. James Speyer

By Tracy Myers

Pittsburgh-born architect and museum curator A. James

Speyer was a leading figure in the cultural life of Chicago for over 30

years. The exhibition now on view in the Heinz Architectural Center highlights

Speyer's architecture, which matured under the leadership of Mies van der

Rohe, and his innovative exhibition design for the Art Institute of Chicago.

A. James Speyer (1913-1986) studied architecture at Carnegie Tech (now

Carnegie Mellon University), graduating in 1934. Like virtually every architecture

school in America at that time, Carnegie Tech still adhered to the Beaux

Arts tradition of architectural teaching, which emphasized the design of

monumental buildings, symmetrical in their organization of rooms and bedecked

with ornament copied from earlier architectural styles.

Dissatisfied with what he considered this tired approach to design,

Speyer spent most of 1934-1937 in Europe, where avant-garde architects

cultivated a dynamic new style of architecture, free of ornament and liberated

from the constraints of symmetrical planning. At the same time, Speyer's

growing friendships with Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., whose father commissioned

Frank Lloyd Wright to design Fallingwater, and Hungarian-born architect

László Gabor, who modernized Kaufmann's department store

in Pittsburgh, brought him into contact with some of the most vocal advocates

of modernism. After meeting with Alfred H. Barr and John McAndrew of the

Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Walter Gropius, founder of the internationally

influential Bauhaus school of design in Germany, Speyer was convinced of

the freshness of modernism and its relevance to contemporary society. By

late 1937, Speyer's "conversion to modernism," as architectural historian

Franz Schulze calls it, was complete.

The moment at which Speyer reached this juncture in his professional

life was one of the great turning points in 20th-century American cultural

history. By 1937, Hitler's genocidal and imperialistic intentions were

clear, and many progressively minded German artists and intellectuals fled

the country in protest and fear of persecution. Walter Gropius emigrated

to the United States to teach at Harvard's Graduate School of Design in

1937, and architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe arrived in Chicago in 1938

to lead the architecture school of the Armour Institute of Technology (now

the Illinois Institute of Technology). Each architect quickly developed

a following, and their students collectively transformed the architectural

landscape of this country.

Speyer decided to study with Mies at IIT, and adopted the Miesian philosophy

that "less is more." Speyer's graduate work was followed by service in

the army from 1941 through 1946, and after his discharge he returned to

Chicago to teach at IIT, which had become the Midwest's leading outpost

of modernism. He also established his own architectural practice in 1946.

The houses in Chicago and Pittsburgh that Speyer designed between 1947

and 1963 bear the deep imprint of Mies van der Rohe. Like Mies's perfected

building form, Speyer's houses are rectilinear structures of exposed steel

beams supporting vast expanses of glass or infilled with brick, all enclosing

open spaces that flow into each other, rather than being carved into discrete,

wall-bounded rooms. These features are evident in the houses Speyer designed

for his mother, Tillie S. Speyer, and for Joan and Jerome Apt, both in

Pittsburgh. For his mother's house, Speyer used a dramatic double-ramped

staircase to enliven the open space that grows from the living room to

the second floor.

|

|

Tillie S. Speyer house, 1963. The palatial staircase has risers

that create a gentle slope to the upper bedroom level.

Although Speyer frankly acknowledged his debt to Mies, he also departed

from his teacher's model in ways that mark his own designs as unique. Whereas

Mies favored black steel and buff-colored brick, for example, Speyer often

used white steel and red brick. More radical were his insertion of a curved

wall of teak in the living room of the house for Stanley G. Harris, and

the use of a round arch to frame the living room fireplace and each of

the three garage doors in the Apt house. Like any good student, Speyer

critiqued what he had been taught, and then turned the lessons to his own

account. In the case of the Apt house, it is tempting to speculate that

Speyer was also responding to local precedent: the round arches in this

Pittsburgh house immediately call to mind the powerful arches of one of

the city's most famous architectural monuments-H. H. Richardson's Allegheny

County Courthouse and Jail.

|

|

The Apt House, 1953. The garage court has gracefully curved

entrances to the parking stalls.

In 1957, after more than a decade of teaching and practicing design, Speyer

was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to study ancient and modern manifestations

of architectural classicism in Italy and Greece. He remained in Athens,

where he also taught architecture at the Athens Polytechneon, until 1959.

Returning to Chicago, he resumed teaching at IIT and expected to re-establish

his architectural practice. Then through a series of serendipitous events,

his career took a decisive-and permanent-turn. In 1961, he was appointed

curator of Twentieth Century Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute

of Chicago, where during a 25-year career he organized, designed, or installed

more than 125 exhibitions.

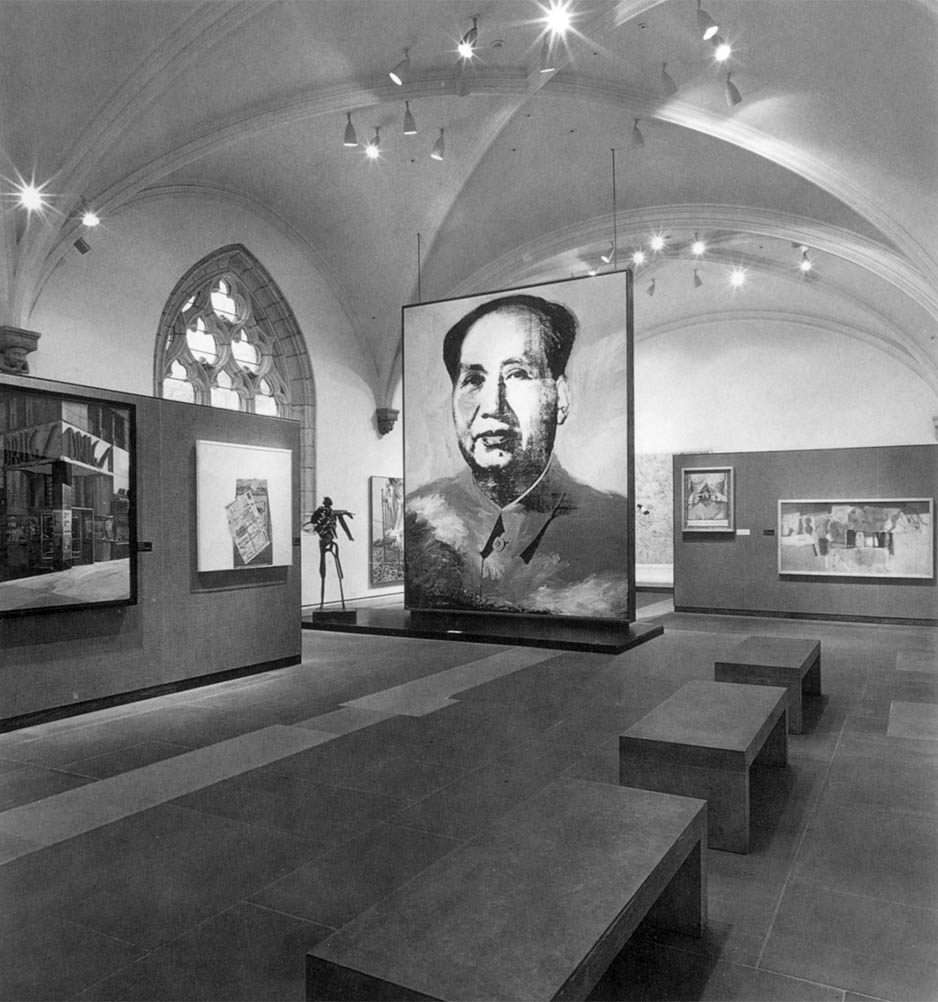

|

Speyer's installation of Andy Warhol's Mao.

Speyer is today better known for his work at the Art Institute than as

an architect, but his approach to exhibition design was a natural outgrowth

of his architectural sensibility. In the vast galleries of the Art Institute,

he combined asymmetrically placed floor-to-ceiling panels with free-standing

partitions of varying heights to create the fluid, irregular spaces found

in the houses he designed. On occasion, he also suspended murals from the

ceiling to further transform the galleries' space. He gained additional

visual variety in his exhibition designs by covering partitions and walls

with painted fabric and placing objects on platforms rising from the floor.

To enable visitors to examine the paintings in his exhibitions more closely

than in typical installations, Speyer often hung the works slightly below

eye level.

Speyer was renowned in the Chicago museum world, and not solely for

his exhibitions and distinctive installations. He enlarged the Art Institute's

collection of contemporary art through unusually well-informed and thoughtful

acquisitions of American and European works, adding nearly 650 objects

during his career there. His retrospective of the work of Mies van der

Rohe in 1968 launched a series of architecture exhibitions that led the

Art Institute to become one of the first American museums to establish

a department of architecture. Together with his house designs and restorations,

these accomplishments comprise the legacy of a keen and passionate intellect.

The Heinz Architectural Center is pleased to bring to Pittsburgh the work

of this multi-talented native son.

Tracy Myers is assistant curator of the Heinz Architectural Center.

Information in this article is derived from essays in the exhibition catalogue

by John Vinci, a co-organizer of the exhibition, architectural historian

Franz Schulze, and Barbara Mirecki. The catalogue, A. James Speyer: Architect,

Curator, Exhibition Designer, is available in the Carnegie Museum of Art

Store.

Franz Schulze will lecture on Speyer on Tuesday, February 6, at 6:00 in

the Museum of Art Theater. On Saturday, February 7, he will lead a tour

of Speyer's two Pittsburgh houses, followed by lunch in the Museum Café.

The lecture is free to the public; the cost of the tour, including lunch,

is $30.00. For additional information, call the Heinz Architectural Center

at 622-5551.

The programs of the Heinz Architectural Center are made possible by the

generous support of the Drue Heinz Trust.

|