Let's not talk about the man who seemed so strange, so implausible, so different from you and me, the man who left the hills and rivers of Pittsburgh for the heights and canyons of Manhattan. In that leap of his from here to there, he seemed to have crossed a chasm into which many don't wish to go, a place that is both alien and frightening, but most of all unknown. It was exactly that unknown terrain that Andy Warhol most favored when he could become the first to scout it out, survey its turf, and map it out for others to follow in his pioneering footsteps. One of his early Pop paintings, Do It Yourself (1962), says it all. However, it is exactly this punctilious swagger combined with the way-cool-dude mode of the swinging 60s that makes Warhol so hip for some and, simultaneously, so unapproachable for others even today, 10 years after his death. For many people who contemplate a visit to The Andy Warhol Museum, a lingering disquiet often prevents them from raversing the front door on Sandusky Street. What will they find lurking around the corner, waiting to jump out and assault their sensitivities?

fact,

this image of the 50-ish Andy, topped with his cheap fright wig, should

best be seen as a symbol of the artist's insecurity and vulnerability:

ashamed and disgusted with his bald pate, Warhol chose those outlandish

wigs to cover up what he considered to be so undesirable. And, as some

prescient shrink might well comment, the omnipresent rug made one focus

on the costume, and not on its wearer. Who among us has not, at one time

or another, wanted to blend into the background rather than stick out like

the proverbial sore thumb? Then there are those lingering questions of

"lifestyle," you know, that old rag about sex, drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll!

While many in Andy's Factory circle chose to imbibe in all three, the artist

himself, like some latter-day alumnus of the Betty Ford Clinic, stood back

from all that, needing to have his astute wits about himself. The 60s was

a time for extraordinary experimentation, the results of which changed

the face of America and the world. For Andy Warhol, he saw these changes

and created an art style which would mirror them. Among his portrait sitters

alone, one finds the architects of the new cultural order: Mick Jagger,

Dennis Hopper, and Truman Capote, just to name a few. For Warhol, subculture

became supraculture as society's renegades became his superstars. Not surprisingly,

today even more than during the 1960s, youthful interest in these now amazingly

60-ish former subcultural heroes is high. Parents may still be terrified,

but the kids love it!

fact,

this image of the 50-ish Andy, topped with his cheap fright wig, should

best be seen as a symbol of the artist's insecurity and vulnerability:

ashamed and disgusted with his bald pate, Warhol chose those outlandish

wigs to cover up what he considered to be so undesirable. And, as some

prescient shrink might well comment, the omnipresent rug made one focus

on the costume, and not on its wearer. Who among us has not, at one time

or another, wanted to blend into the background rather than stick out like

the proverbial sore thumb? Then there are those lingering questions of

"lifestyle," you know, that old rag about sex, drugs, and Rock 'n' Roll!

While many in Andy's Factory circle chose to imbibe in all three, the artist

himself, like some latter-day alumnus of the Betty Ford Clinic, stood back

from all that, needing to have his astute wits about himself. The 60s was

a time for extraordinary experimentation, the results of which changed

the face of America and the world. For Andy Warhol, he saw these changes

and created an art style which would mirror them. Among his portrait sitters

alone, one finds the architects of the new cultural order: Mick Jagger,

Dennis Hopper, and Truman Capote, just to name a few. For Warhol, subculture

became supraculture as society's renegades became his superstars. Not surprisingly,

today even more than during the 1960s, youthful interest in these now amazingly

60-ish former subcultural heroes is high. Parents may still be terrified,

but the kids love it!

|

|

|

|

Well, if you literally don't

go there, you and your children will never see all the things that bespeak

postwar culture and that Andy Warhol expressed so vividly in his oh-so-American

art. The Andy Warhol Museum may not be terra firma, but once you enter

it, definitely it will not be terra incognita. What you will see in front

of, around, and behind every pillar is a mirror of yourself and the world

in which you live which, at base, was Andy's world. "Don't go there," as

the street kids would say, "Not!"

|

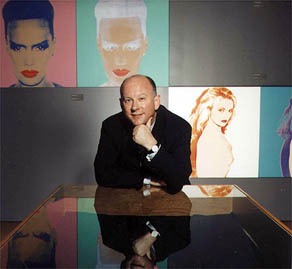

Thomas Sokolowski is director of The Andy Warhol Museum.

Reporters and the general public increasingly see the museum as a place to find out about the meaning of iconic images and the popular symbols of everyday life. Curators Mark Francis and Margery King and director Thomas Sokolowski are often asked for comments on Warhol's work in its relation to pop culture, and for images by Warhol to illustrate news stories. Thus the public's interest in knowing more about the symbols of daily life has made the museum into an accessible center for the study of popular culture.

Warhol rose from poverty by interpreting the ordinary details of life, from soup cans to telephones and shoes, for a mass audience. As a famous artist he created portraits of celebrities from Princess Diana to Chairman Mao and O.J. Simpson and Mick Jagger, turning them into icons for our time. His work marked him as the consummate artistic spin doctor and visual interpreter of the American Dream. Who better could chronicle the obvious, and understand its artistic potential for the mass market?

What does the pink flamingo signify after four decades of use as a lawn

ornament? Why did the Volkswagon beetle become an icon of the popular imagination

and then return to the market place? The art experts at the Warhol do not

claim to know all the answers to the visual legacy of contemporary popular

culture. But The Andy Warhol Museum with its emphasis on one artist's interpretations,

and its resources for further study, are increasingly seen by many

people as one place to begin the search.

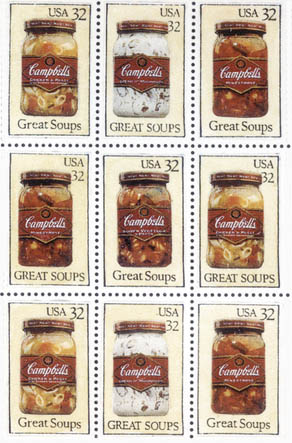

Thousands of professional and amateur artists and writers entered Campbell's "Art of Soup" contest, which the company dubbed "the search for the next Andy Warhol."

Campbell's announced the winner in October at the museum. Dino Sistilli,

a 70-year-old retiree from New Jersey, received the grand prize for his

sheet of commemorative postage stamps featuring Campbell's newest product-soup

in glass jars. He received $10,000 and 100 shares of Campell's Soup stock.

Sistilli's artwork, along with several other contest submissions, was displayed

at the museum last fall.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |