Back When America Sang |

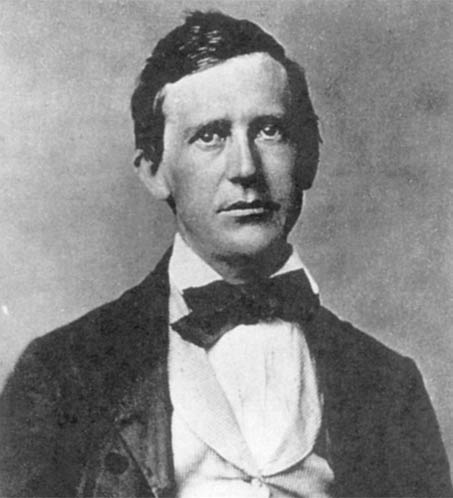

Doo-Dah!: Stephen Foster and the Rise of American Popular Cultureby Ken EmersonSimon & Schuster, 1997, 400 pp., $30.00 |

Reviewed

by Victoria Cole

Reviewed

by Victoria ColeJust when the Chicken Little tone of our current culture wars promises to become unendurably predictable, along comes Ken Emerson. His Doo-Dah!: Stephen Foster and the Rise of American Popular Culture opens a window to let in the much-needed fresh air of historical perspective on our stuffy debates over "multiculturalism" and "diversity." By the end of this engaging work, the reader's view of our current situation includes an understanding that racial tension, cultural turf wars, and the intermingling of "black" popular culture with "white" popular culture is as old as our republic, doubtless older.

Not the least pleasure of this perspective is the author's own breezy prose. A rarity in this age of academic specialists and critically top-heavy scholarly discourse, Emerson has produced a readable, often funny depiction of the origins of American popular music. Along the way he surveys the landscape in which popular culture engages us, our expectations and prejudices.

And what a scene! Emerson plunges us straightway into the same chaotic cultural melange that so intrigued observant 19th-century visitors to our shores like Dickens and Mrs. Trollope. Stephen Foster's native Pittsburgh emerges as a brawling, grimy, vivid place.

Still nearly a frontier city already grappling in the 1820s with problems of ethnic conflict which endure to this day, the inhabitants of Foster's Pittsburgh were a boisterous lot. They engaged in the kind of street expressions of politics, celebration, or just plain mob violence which make our current public culture pale in comparison. Politics often led to fisticuffs, the right song could emotionally sway a crowd from ugliness to laughter, and people fought in the streets to get to hear Jenny Lind. It's a long way from this to the careful correctness characterizing the choreographies of, for example, a party convention today.

Foster was right in the thick of it, and his response to this rollicking milieu forms the core of Emerson's book. Unfortunately, however, Emerson's leading man simply cannot sustain the reader's interest for very long. Foster emerges as something of a wash-out, however gifted a tunesmith. About halfway through Doo-Dah! one can't help noticing that Foster himself wasn't an interesting man, and his life not terribly engaging in the telling. A drop-out, a disastrous businessman, and a bit of a mama's boy, Foster survived in his vocation by adopting two very successful contemporary song styles-blackface minstrel songs and the genteel parlor ballad. This he did very well.

Emerson is at his best in his offhand discussions of Foster's dubious relationship to these two styles. It is astounding how drippy and downright necrophilic so many of Foster's genteel lyrics sound today. His white heroines ("Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair," "Little Belle Blair," "Gentle Annie," as well as assorted mothers and wives) are dreamy, drifty, or dead. Foster sentimentalized women in order to organize the pain in his life, including a failed marriage, and his beloved mother's death.

Much of the blackface material today merely embarrasses. Emerson's clear eye on the racist "minstrel" songs reveals to all today's racial doom-sayers that we have indeed traveled quite a distance from the days when white boys in blackface stood around caroling how they're "longing for de old plantation."

If anyone still needs a demonstration of the difference between high culture and popular culture, think how infinitely more subtle, complex, and engaged are Mark Twain or even Harriet Beecher Stowe with issues of race in America than these squirmy-making lyrics.

Emerson labors mightily to retrieve some genuine sympathy for the black man from Foster's self-proclaimed "Ethiopian" tunes. But he doesn't gloss over their appalling aspects. Yet it is true that from this muddy spring the author traces the beginnings of jazz, which has emerged in our century as popular music's most interesting and integrated form.

It was one of the tragedies of the composer's short life that because he sold the copyrights to his work for a pittance, he never profited from his own fame. Just how famous was he? Suffice it to say that Foster songs were translated into Chinese in his lifetime. Tradesmen hummed Foster songs on the job, and opera singers sang them as encores.

However discredited Foster's vision may be today, we may look back and envy the sheer participatory glee which his audience brought to this music. For this music sold, sold universally. Not recordings, videos, or second-hand interpretations. Rather, middlebrow America went out and bought the sheet music and stood around the parlor piano to sing it, together. Those with no piano picked up the tunes on the street corners or in cheap cafés.

Foster's music, with all its prettifying lyrics and bald stereotypes, brought us together in a way that all the CDs in the world will never do. That is because Americans a century ago were a singing people. When in 1855 Walt Whitman penned "I hear America singing" he referred to Foster's America. After finishing Ken Emerson's Doo-Dah!, a reader would be well-advised to go over to the piano and sing through one of Foster's tunes. It is in the singing that these songs transcend their myriad simplifications and become a genuine expression of the life and energy that were once ours by birthright, before we became a nation of passive listeners.

Victoria Cole is manager of Performing Arts at Carnegie Museums of

Pittsburgh.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |