While numerous exhibitions and books have focused on the 1939 New York World's Fair and its history, Drawing the Future is the first to showcase the works of designers and renderers whose job it was to actually create the "World of Tomorrow." These beautiful documents of the design process, created as the Fair was fleshed out from 1936 to 1938, portray buildings, displays and objects that were considered for inclusion in Flushing Meadows. Some were built as shown while others changed considerably, or completely, on their way to temporary reality. A number of the projects presented here were never realized, and exist solely in these renderings. Drawn before a single supporting pile was driven, and years before the first lucky family entered the Fair's magical precinct, they are the most accurate remaining record of the intentions of the architects and designers who created this, the greatest of all 20th-century world's fairs.

The guidelines set by the New York World's Fair Board of Design for its two-year World of Tomorrow were socially conscious, high-minded and forward thinking. Although "unity without uniformity" was the original plan for the mostly temporary structures to be erected, the resulting architectural cacophony that still defines the Fair's image in the American imagination was visually discordant but viscerally harmonious. It was a jumble of streamlined modern and vaguely classical buildings, intermingled with midway attractions, titanic typewriters, gigantic cash registers and enormous electric razors. Linking displays of the labor-intensive but honorable past, with exhibits that promised a comfortable and neatly ordered future, it was at once pedantic, strange and inscrutable. With the brilliantly white and soaring Trylon, and waterborne Perisphere at its hub, and boulevards of buildings radiating outward in zones of gradually intensifying color, the Fair was more Oz than Kansas-or Iowa, Illinois, New Jersey or New York, and Americans loved it. It was immortalized in more gee-whiz photo albums than any single event before and possibly since, and its loopy, swooping, spiky image still lives in the minds of scores of people born long after its demolition.

Organized on 1,200 acres of swampy landfill in Queens, the 1939 World's Fair was born with a 19th-century plan and a futuristic slogan-"Building the World of Tomorrow with the Tools of Today." Envious of the financial success of Chicago's 1933 "Century of Progress" exposition, the Fair was conceived in 1935 by powerful New York businessmen as a hopeful boost to the Depression-wracked local economy. It was conceptualized in 1936 by the self-anointed "Fair of the Future" Committee, led by distinguished historian and critic Lewis Mumford, with the intention of avoiding the traditional exposition focus on advances in technology in favor of exhibits of genuine social value. Architecture at the Fair was to find its form in public improvement and American cultural enrichment, and in the application of new science for its positive impact on the average working man and his family.

-Adapted from the introduction to the catalogue.

The 40 works in this exhibition are drawn from 391 design drawings, watercolors, architectural studies and photographs donated to the Museum of the City of New York in 1941 by the World's Fair's legal department.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue were made possible by the generous support of Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf, and Lisa and Eric Green.

The programs of the Heinz Architectural Center are made possible by the generosity of the Drue Heinz Trust.

Here are details about the five drawings shown on pages 41-44.

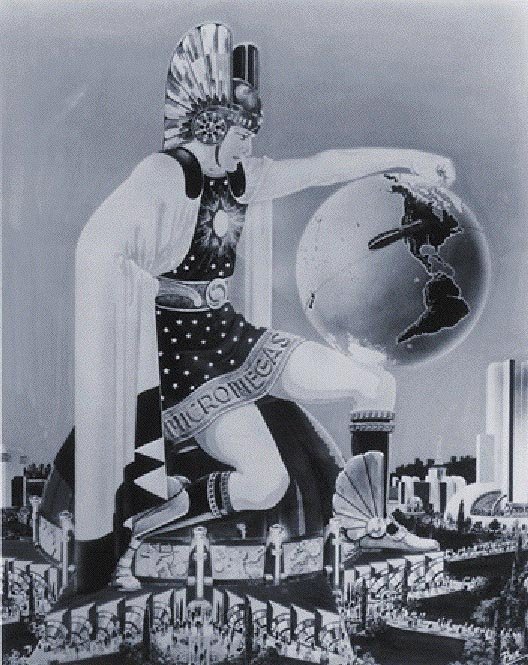

Frank Paul, designer and delineato; airbrushed tempera and watercolor on board

Many of the realized buildings from the Fair clearly took cues from futuristic visions promulgated by science fiction pulp magazines of the year. In this fantastical scene, a warrior clad in Roman garb sits astride a domed pavilion with a star-shaped base reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty's architectural foundation. Frank Paul, one of the principal science fiction illustrators of the day, perhaps took his revenge on an unresponsive Board of Design with his 1939 cover of Science Fiction No. 2 showing the Trylon and Perisphere being attacked by invading spaceships.

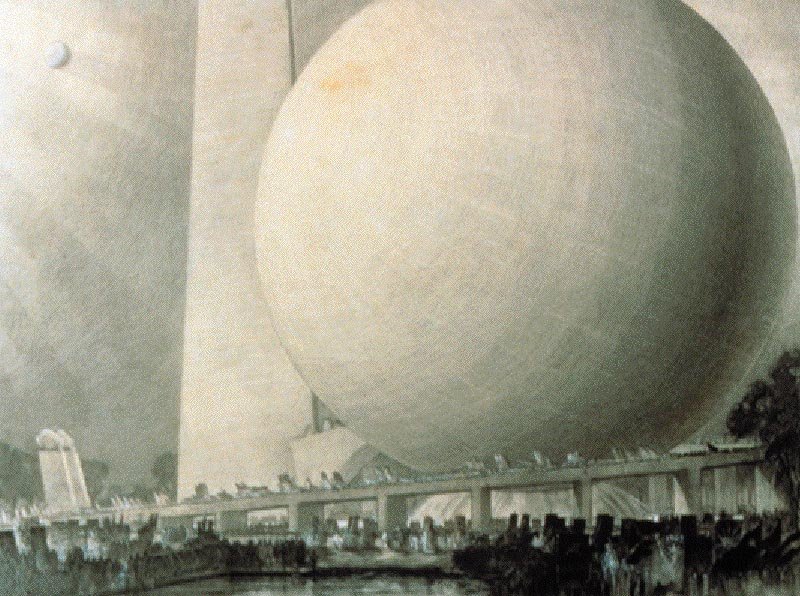

Hugh Ferriss, delineator; Harrison and Fouilhoux, architects; charcoal and gouache on board

More familiarly known as the Trylon and Perisphere, this instantly recognizable symbol of the Fair consisted of a 610-foot-high pyramidal tower (the Trylon) and a spherical structure 180 feet in the diameter (the Perisphere) set within an 18-foot-wide, 950-foot-long ramp (the Helicline). The Perisphere seemed to float above a reflecting pool, elevated 17 feet on eight tubular steel columns and ringed by fountains.

Street Elevation, Food Exhibit

Building., 1937

Lloyd Morgan, delineator; Leonard Schultze and Archibald Manning Borwn, architects; airbrushed watercolor, ink and pencil on board

"The Heinz Dome" was originally designated as the Fisheries exhibit. Murals on the facade and dome by Dominico Mortellito reflected both the building's original theme and its eventual function as a food pavilion. In its display, Heinz demonstrated hydroponic cultivation in the Garden of the Future and gave away approximately six million of its famous pickle pins, which had been introduced at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

(Dawn of a New Day, Queens

Museum, 1980.)

Plaza (study), 1936

John Wenrich, renderer; watercolor and pencil on board

John Wenrich, Theodore Kautzky, Hugh Ferriss and Chester Price were the Fair's four "official delineators." Employed by the Fair's Board of Design and working on the Fair grounds in communal drafting rooms, these artists were responsible for the visual presentation of the architects' ideas, and occasionally designed various other elements or incidental Fair structures. The thematic visual approach to the Fair is already established in this 1936 imagined view of a pubic space, showing throngs of people, flags streaming and greenery amidst geometric buildings emblazoned with giant murals.

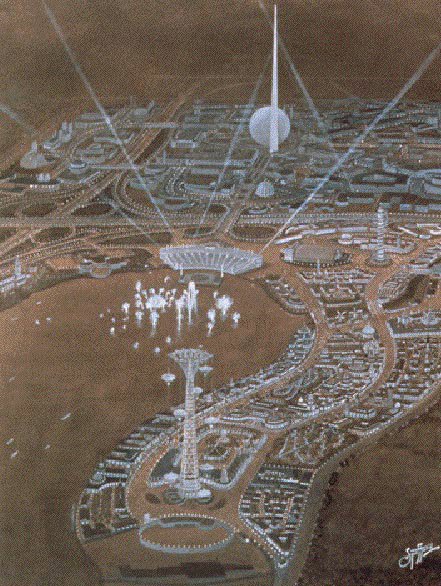

Bird's-eye-view of the Fair, c. 1939

E.W. Spofford, artist; watercolor, gouache and ink on paper

Despite early efforts of the Fair's organizers to stress the event's

educational aspects, the Amusement Area, a 280-acre area around Fountain

Lake, proved one of the Fair's most popular features. In the foreground

of this bird's-eye view is the Parachute Jump, sponsored by the Life Saver

Company and invented by retired aviator James H. Strong. Half a million

visitors jumped the 250-foot free fall from the 360-foot-high tower, which

was moved to Coney Island in 1940 when the Fair closed. The Billy Rose

Aquacade, visible in the upper middle, drew one out of every six Fair visitors

with its bevies of swimming, dancing and singing women.