"This new posture doesn’t mean museums were wrong all these years about T. rex," says Mary Dawson, curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, in reference to the previously accepted vertical posture. "Paleontologists have simply begun looking at T.rex more as a living, moving animal than as a static museum trophy." Indeed, the horizontal posture reflects what scientists now see as T. rex’s likely locomotive posture, but Dawson says the animal could very well have assumed the older, vertical position when at rest.

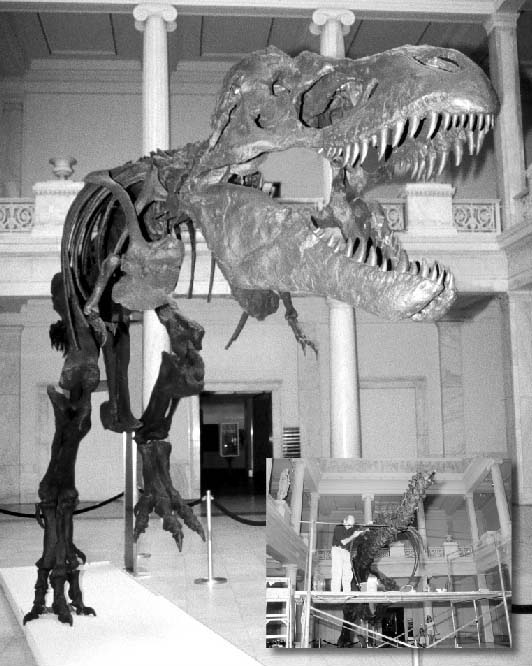

A new cast of T. rex, in the active, horizontal stance, was assembled over the summer by museum staff in the Hall of Sculpture, and it will remain on display through January 4 as part of the exhibit The Age of Dinosaurs Lives On. Museum visitors were able to watch as the new T. rex took shape over two months, vertebrae by vertebrae and rib by rib.

The specimen was purchased by the museum from Research Casting International, which cast it from an original T. rex at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana.Norman Wuerthele, manager of the museum’s preparation laboratory, and preparator Richard Kissell, assembled the specimen and positioned it according to the latest scientific information.

"Even though the cast came with the legs and pelvis already put together, assembling it was more difficult than we expected," says Wuerthele. Without a blueprint, he and Kissell had to determine the order of the specimen’s bones, and also cut and shape the ribs. "And we built it knowing that we’d eventually have to dismantle it," Wuerthele continues, "so we used screws to attach most of the bones, instead of epoxy glue."

Among the hundreds of curious onlookers who witnessed the assembly of the T. rex cast was welder Kent Frazee. Returning with his own special equipment, he bent and cut the steel framework onto which the specimen’s arms were then attached, and saved the museum staff time and money that would have been spent hiring a contractor to do the job. Frazee has a special connection to T. rex at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, for he was once employed by Anderson Welding, the company that did the welding on the museum’s original T. rex in the 1940s. He says that a photograph of that specimen hangs on the wall at Anderson headquarters.

That original T. rex, on exhibit in the museum’s Dinosaur Hall, will be remounted in an active, horizontal position as well, when the hall is renovated over the next few years. The two T. rex specimens will then be exhibited sparing with each other in a lifelike situation.

The museum’s older T. rex is the type specimen—the individual on which the original scientific description of T.rex was based, and to which all others of its kind must be compared. In other words, the Carnegie’s T.rex is the official T. rex, which makes it all the more important for Carnegie Museum of Natural History to do right by the animal and show it in a posture that reflects its lifestyle, and the latest scientific thinking.

Kathryn M. Duda is associate editor of Carnegie Magazine.