Keeping Up with the

Miniature Railroad & Village

Keeping Up with the

Miniature Railroad & Village Keeping Up with the

Miniature Railroad & Village

Keeping Up with the

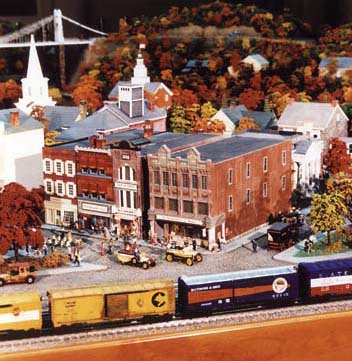

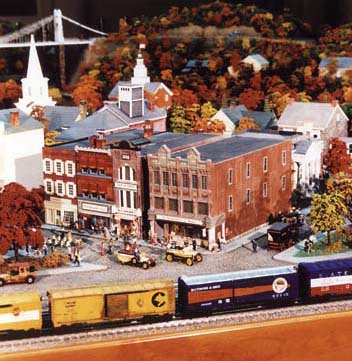

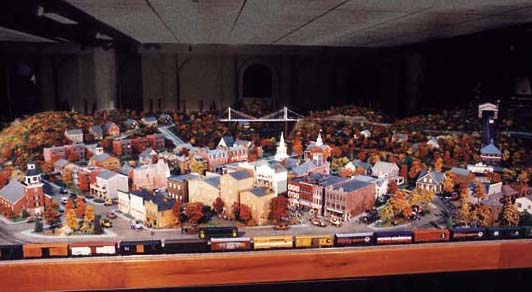

Miniature Railroad & VillageAt 30 by 83 feet, with five Lionel trains, two trolleys and four boats running, it is a big, varied exhibit. While it doesn’t claim to be the largest train layout, the MRR&V is unmatched anywhere for its appeal and class. For one thing, it has a mission that provides it with integrity—it interprets Pennsylvania’s industrial and social history in the first decades of the 20th century, when science and manufacturing were impacting small towns to shape the modern society we live in. The transportation is here—early automobiles, trucks, trains, trolleys, inclines, airplanes—as is the industry—a large steel mill, a coal mine, stone quarry, brickworks and sawmill. All are signs of the basic industrial powers that transformed Pennsylvania. Juxtaposed against the industrial forces of change are realistic small-town scenes—the general stores, local hotels, businesses, apartment houses, "company" houses for workers, churches, library, ballfield, visiting circus, and railroad station. In the countryside the autumn fields are rich with produce and the details of daily life on the farm.

It is a vision of real life, set forth in such convincing detail that the visitors walk around it like giant gods, inspecting and commenting on every human action, from the girl on the backyard swing to the mother rocking the baby, the men loading barrels on wagons and sawing wood, the suffragettes parading on Main Street, and the fisherman casting his line. This world of little figures is in motion—there are 97 animated figures, each with its own tiny motor. Night falls, the lights in the town and countryside go on, but soon morning comes again. At all times of day the trains and the riverboats continue their transportation routines.

The greatest changes to this miniature world occur every few years, when the prime movers behind the scenes, coordinators Michael Orban and Patricia Everly, refresh the whole vision with a new look—such as a seasonal change to all the trees to reflect a colorful autumn landscape, or add a large component like a steel mill. The smaller adjustments to the display go on continuously, as new details are added, usually reflecting even more Pennsylvania history than before.

A recent example is the addition of the Pittsburgh Courier building,

the site of Pittsburgh’s famous newspaper for African-Americans. This structure

on Center Avenue in the Hill District was for a long time the home of the

newspaper started in 1910, and still publishing today. A crusading weekly

that advocated racial equality, the Courier achieved a circulation of 400,000

by 1947. But this building was later demolished, and the model had to be

reconstructed from views in old photographs to add this story to the experience

of the Village.

Volunteers will point out, for example, Andrew Carnegie’s youthful visits to Colonel Anderson’s library in Allegheny City in the 1850s—a library that is recalled in a miniature storefront based on an old illustration. The first courthouse in Allegheny City is also reconstructed from an old print. There is a good deal of Pittsburgh’s North Side in this exhibit. The North Side was formerly known as Manchester and Allegheny City, and the Buhl Planetarium itself was named after Allegheny City businessman Henry Buhl, Jr. Years ago the "Honeymoon House" in which Buhl once lived with his wife (1511 Buena Vista Street) was reproduced as a model, and other models include the Mexican War Street house, 1201–26 Resaca Place, and now restored houses on 1300 Liverpool Street.

The North Side business

district of East Ohio Street is seen in miniatures of extant buildings

at 413–15, 520 and 531. This last is now the Photo Antiquities building,

one of the key restored buildings on the street.

The North Side business

district of East Ohio Street is seen in miniatures of extant buildings

at 413–15, 520 and 531. This last is now the Photo Antiquities building,

one of the key restored buildings on the street.

Pittsburghers will recognize their familiar Monongahela Incline, and the East Street Bridge, and some will remember the now-gone Point Bridge. People from Lawrenceville will note their old Number 9 Firehouse at 5255 Butler Street in the Village.

Visitors from other

towns also enjoy familiar landmarks. The Donora Post Office of 1929 is

a landmark in that town, as are the Lark Inn in Leetsdale, the Rachel Carson

homestead in Springdale, and Searights Tollhouse along Route 30. Homestead

residents will recognize their railroad station, and people who know about

Old Economy will recognize the St. John Lutheran Church in Ambridge. McKeesporters

will see their Watchtower, and everyone should recognize a classic turn-of-the-century

"company" house—generic workers’ housing which in this case is based on

houses in Webster, Pennsylvania (across the river from Donora, on the Monongahela).

Visitors from other

towns also enjoy familiar landmarks. The Donora Post Office of 1929 is

a landmark in that town, as are the Lark Inn in Leetsdale, the Rachel Carson

homestead in Springdale, and Searights Tollhouse along Route 30. Homestead

residents will recognize their railroad station, and people who know about

Old Economy will recognize the St. John Lutheran Church in Ambridge. McKeesporters

will see their Watchtower, and everyone should recognize a classic turn-of-the-century

"company" house—generic workers’ housing which in this case is based on

houses in Webster, Pennsylvania (across the river from Donora, on the Monongahela).

Many of the original models are based on structures in Brookville, and

full documentation does not exist for all the sources. But Brookville itself,

located north of Pittsburgh on Interstate 81, today has a charmingly restored

downtown that reveals a lot about early 20th-century Pennsylvania. Perhaps

somehow the celebration of the Jefferson County seat in miniature by creator

Charles Bowdish, starting in the 1920s, eventually helped the town itself

achieve the remarkable restoration of the real thing.