A loud, sweet, clarion song, followed by a series of distinctive, sharp, metallic call notes, rings out from a nearby wooded ravine. It is a bright, chilly morning in early April, and a male Louisiana Waterthrush, absent for nearly eight months, has returned from distant tropical wintering grounds in Mexico, Central America or the West Indies to reclaim its breeding territory along Powdermill Run. The waterthrush is a welcome sign of spring's arrival, and it also could be one of the bio-indicator species that environmental analysis depends upon.

In Pennsylvania, acid precipitation and acid mine drainage have changed the chemistry of thousands of miles of small headwater streams, often with devastating consequences for aquatic life. At Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History's 2,000-acre biological station in the Laurel Highlands, researchers have begun a field study to find out how the loss of macroinvertebrates in acid-polluted streams affects the Louisiana Waterthrush. The study, partially funded this year by a grant from Pennsylvania's Wild Resource Conservation Fund, may eventually help with efforts to protect and restore forested headwaters throughout the region.

The Louisiana Waterthrush is not a true thrush at all, but rather an unusual member of the wood warbler family, a group of mostly very small, brightly colored, arboreal ("of the woods") songbirds. At just six inches long, and weighing less than an ounce, the waterthrush is still twice as large as most other warblers. It is not colorful, being brownish above and white streaked with brown below. Its most conspicuous features are its long, pinkish legs and a bold white stripe over each eye. It is a ground-foraging, ground-nesting bird that ventures into the trees mostly when it needs an elevated perch from which to broadcast its wild, ringing song, or to hear the answering songs and calls of other waterthrushes, over the loud rush of fast-flowing water below.

The bird's scientific name, Seiurus motacilla, is derived from Greek and Latin words meaning bobbing or wagging tail. The species was once known by the common name "Water Wagtail," which is another reference to its habit of continually teetering as it walks deliberately along the edge of the stream, or perches on rocks and logs in the stream, searching for food. This unusual locomotion, which is shared by some sandpipers and a variety of birds that forage along the edges of streams, rivers and ponds, may, by continually changing the waterthrush's angle of vision, improve its ability to spot small, often cryptic, aquatic prey through the glare of sunlight on the water's surface.

Although its common name suggests that it is a southern bird, the Louisiana Waterthrush actually breeds throughout the eastern United States, as far north as southern Maine. It is widespread in Pennsylvania, being especially common in the mountainous sections, where many small, rushing, cobble-strewn streams provide it with an abundance of nesting and foraging sites.

A serious threat to the ecological integrity of the stream habitats preferred by waterthrushes in Pennsylvania, and throughout the Appalachian region, is acid discharge from countless abandoned coal mines and acid precipitation resulting from widespread air pollution. Landmark studies conducted throughout the Laurel Highlands, spearheaded by researchers from Pennsylvania State University, have clearly shown that while acid-impacted headwaters often retain their scenic beauty, they invariably lose biodiversity-many aquatic organisms simply cannot survive or reproduce in them. As a result, the protection and restoration of forested headwaters has become a high priority for federal, state and local natural resource agencies, as well as for grassroots watershed associations.

In our study at Powdermill, we hope to learn how stream pollution affects waterthrushes and, in turn, if waterthrushes might be able to serve as a sort of "canary-in-a-cage," or bio-indicator, for providing information about the condition of headwater stream habitats throughout the region.

In order for the Louisiana Waterthrush to be a useful bio-indicator of headwater stream quality, however, differences or changes in stream quality must have observable, and to a large degree predictable, effects on the species. For example, in streams where acid pollution has reduced the food supply for waterthrushes, fewer males might establish territories, territories might be established later in the spring and more often by inexperienced males, territorial males might be less successful at attracting mates, or mated pairs might be less successful at rearing young, compared to waterthrushes in unpolluted sites.

A headwater stream on Powdermill called Laurel Run is impacted by heavy drainage from two abandoned coal mines. Data collected by Pennsylvania's Department of Environmental Protection and the Loyalhanna Watershed Association show that it is very acidic (pH 4.0-5.5), has reduced macroinvertebrate diversity and abundance, and supports no fish populations. The fact that Laurel Run is slated for reclamation beginning this year, through projects co-sponsored by the above two agencies, has given our study an added dimension-the opportunity to assess waterthrush populations in Laurel Run before and after remediation efforts.

In contrast to the situation in polluted Laurel Run, numerous studies conducted by faculty and graduate students from the University of Pittsburgh show that Powdermill Run is a pristine stream that supports a large and diverse macroinvertebrate community, as well as viable populations of many kinds of fish. This means that Powdermill Run can serve as a "reference" or "benchmark" site both for gauging the effects of stream pollution in Laurel Run and, eventually, for evaluating the effectiveness of reclamation efforts there.

The primary objectives in our first season were to determine the number of territorial males and breeding pairs of waterthrushes along equivalent reaches of Powdermill Run and Laurel Run, to find the nests of all breeding pairs, and to document the success or failure of those nests. Last year, with a help from a hard-working and dedicated team of student interns and other volunteers, we logged more than 2,500 observer-hours in the field trying to meet these goals.

A male waterthrush advertises his territory ownership by singing continually until a female arrives on his territory, usually within a week or so. Early in the season, territorial males must be alert for the arrival of prospective mates, and at the same time vigilant against intruding males, either neighboring males trying to enlarge their territories, or late-arriving males trying to usurp one. In the first weeks of our study last year, we witnessed several dramatic aerial chases and vocal contests between territory-holders and would-be challengers.

We used the males' territorial behavior to our advantage. To begin with, by listening for and mapping the location of singing birds early in the season, we were quickly able to make a rough census of the number of territorial males in each stream and the approximate upstream and downstream limits of each male's territory. Conspicuous, sequentially numbered flags were placed at 50-meter intervals for a distance of 3 kilometers along both streams. As with many other riparian species, waterthrushes defend territories that are long (300-400 meters) and narrow (less than 100 meters), and which follow closely along the stream's contour.

To ensure accuracy, we marked each bird with a serially numbered leg band and a unique combination of colored plastic leg bands. The colored leg bands would enable us to identify individual waterthrushes at a distance, by using binoculars.

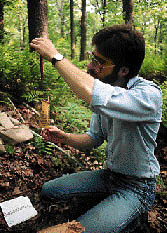

But in order to mark the birds, we had to catch them. Again we took advantage of their innate territorial behavior. After stretching a mist net across the stream within a male's territory, we broadcast another male's song from a concealed tape-recorder placed next to the net. In about half of our attempts, territorial males responded immediately to the phantom intruder, and were caught in our net within minutes of hearing the tape-recorded song. Many other times, however, we watched in frustration as males skillfully avoided flying into our net, or flew in only to bounce out again. Because we did not want to cause undue disturbance to the birds, we discontinued taped song playback if it was not effective within about the first 20 minutes. As the nesting season wore on and males became involved in the female's nesting activities, song playback became a much weaker stimulus.

With a waterthrush in-hand, we examined its plumage to determine whether it was an inexperienced first-year or an older, experienced breeding bird. Retained juvenile wing and tail feathers were the mark of first-year birds, those hatched in the previous nesting season. We measured and weighed each bird, recorded its breeding condition, and released it back into its territory within 10 minutes of its capture. For convenience we banded all males with the numbered band on their right leg and a combination of two color bands on their left leg.

Once a number of the males in our study areas had been caught and banded, beginning with the first one April 27, we quickly turned our attention to locating active nests. They are typically found in cavities among exposed roots and vegetation overhanging an eroded, vertical streambank, usually less than a meter from the surface of the stream. In one case, a "bank" created by soil adhering to the roots of a wind-thrown tree near the stream was used.

Finding waterthrush nests was a very important part of our study and an unofficial rite-of-passage for the project's volunteers and interns. But there are many other things to discover at Powdermill in the springtime, and these easily distracted us from time to time-a newborn fawn nestled in a bed of woodland flowers; tanagers, warblers, grosbeaks and other colorful migrants foraging low in the trees on an unseasonably cold mid-May morning; a waterthrush pair scolding a young black bear for running through their territory.

After a waterthrush nest was found, it was checked every other day or so. If it contained nestlings, we had a good chance to catch the female parent, and also the male, if he had not been caught using song playback earlier in the season. After experimenting with different net arrangements, we settled on placing one net upstream and one net downstream, each about 10 meters from the nest. This enabled us to intercept the waterthrushes as they flew up or downstream from the nest on foraging trips for their young, while avoiding unnecessary disturbance at the immediate nest site. The waterthrushes were so dedicated to their parenting duties, that our capture and handling of them never caused them to abandon their young.

We banded the nestling waterthrushes when they were seven to nine days old. They fledged when they were just 10 days old and able to make only short, weak flights. For the next week or so, until the young were strong enough to follow after their parents, the adult waterthrushes really had their work cut out for them, as all birds do once their young leave the nest. Instead of being able to make direct trips back to the nest with food, they had to keep track of up to five young that had moved different distances and directions from the nest.

By mid-July, last year's crop of waterthrush young had reached adult size and were mostly independent of their parents, who by this time were undergoing a complete molt of the feathers in their by-now ragged plumage. Within the next few weeks, all the waterthrushes had begun their migration to distant neotropical wintering grounds, and our first field season was behind us.

Over the course of less than four months we located a total of 16 territories, banded 26 adult birds, found and monitored 11 nests, and banded 35 nestlings. In addition, we collected preliminary data on waterthrush foraging behavior, and on differences in the diversity and abundance of macroinvertebrate prey available to them in the two streams.

While not definitive, results obtained in 1996 point to a number of differences that may be related to acid pollution in Laurel Run. There were 11 territories along Powdermill Run, compared to only five on Laurel Run. The Powdermill Run territories were smaller and contiguous; the Laurel Run territories were larger and disjunct. Territories were established about two weeks earlier in Powdermill Run than in Laurel Run. Ten out of 11 males in Powdermill Run attracted mates, and all of these pairs successfully fledged young. In Laurel Run, only two out of five territorial males appeared to be mated, but both of these pairs were successful at rearing young.

By now we are halfway through another field season, and we will soon be in a much better position to draw conclusions about the effects of acid pollution on the breeding biology of waterthrushes at Powdermill. But the study will not end there. I am currently pursuing a collaboration with two colleagues, Robert Brooks from Pennsylvania State University, and Terry Master from East Stroudsburg University, who have been studying the effects of other environmental factors on waterthrush populations elsewhere in the state. Pending funding, we plan to begin a joint research study in 1998 to assess the effects of a number of environmental stressors, including acid pollution, stream sedimentation and forest loss and fragmentation, on populations of waterthrushes across Pennsylvania.

Ultimately, we think that this multi-faceted songbird, with its thrush-like appearance, sandpiper-like locomotion, and trout-like eating habits, can tell us a lot about an ecosystem that is the sum of a great many parts.

Robert Mulvihill is a field ornithologist for the section of Birds at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.