John Warhola, Andy's older brother, suspects that Andy would say, if granted heavenly reprieve to return to earth and see The Andy Warhol Museum: "Gee... that's great. Wow." It's hard to argue with that. Andy always protected himself in public with cleverly evasive expressions when he was asked to say something memorable. But critics of American art and culture have learned in the past decade to search beneath the surface of his art to see a whole lot more going on than Andy ever confessed to. Looking after the meaning of Warhol's artistic legacy is becoming a minor industry in cultural interpretation.

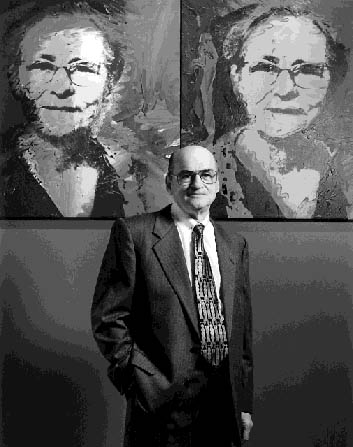

Andy Warhol (1928-1987) died 10 years ago, and many people still have a hard time thinking of him as absent. I spoke to Vincent Fremont, one of Warhol's closest New York friends, and to Andy's older brothers, Paul and John, about what Andy would say about the last 10 years in which his art has remained in the public eye. They were full of insight.

Fremont worked with Warhol from the late 60s on, helped found the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., and is now the exclusive sales agent for that foundation. Fremont says that a few art historians "tried to bury Warhol" 30 years ago. "But he was first and foremost an artist, and the import of what he did only comes to light more" as time passes. "His 60s work stays fresh, and he would have been pleased at the sale of his collection." Even though Andy announced, "' I can't draw,' his sketchbook drawings are fantastic," says Fremont. "Artists in their 30s and 40s today are amazed by them."

Fremont still thinks of him "as one of the most intuitive people I ever met. He could put his finger on things-could get to you, and to the press-with ideas, like the idea of celebrity. He was at the right place, at the right time."

But a decade is usually time enough for any reputation in contemporary art to collapse-and Warhol, so preoccupied with the images of a transient popular culture-seemed a prime candidate for disappearance. But it has not happened. In Pittsburgh The Andy Warhol Museum has become a stabilizing influence on his reputation, and a long-term guarantee of his artistic survival. Fremont notes that Europeans often visit the Pittsburgh museum first on an American tour, which they find easy to do because in Europe going from city to city to see art is the normal practice. The museum is also the source of new perspectives on Warhol's art, such as the exhibition now being organized by Assistant Curator Marjory King, demonstrating Warhol's influence on fashion from the 60s through the 80s. The exhibition opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York this fall, and will subsequently be shown at the Andy Warhol Museum.

Andy would also have said "Wow" to the first issue of a new journal of art history entitled Religion and the Arts published by Boston College. The Fall 1996 issue (Volume 1, Number 1) has a special feature on Andy Warhol containing four views of the religious content of his art. The last essay, by Jane Daggett Dillenberger of the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, is entitled "Warhol and Leonardo in Milan," and makes the point that Leonardo da Vinci's famous Last Supper, made banal by generations of copyists in printed replicas until it had become a visual cliché, was given new life and meaning by Warhol in his last exhibition. Having made over 100 works of art based on this renaissance masterpiece, including many pieces of immense size ranging between 25 and 37 feet in length, Warhol exhibited 20 of them in Milan one month before his death. Concludes Dillenberger:

"The Last Supper paintings formed one of Warhol's largest and most profound series. It is also one of the largest groups of paintings with religious subject matter by an American artist of our century, indeed, of our 300-year history. Only John Singer Sargent's murals for the Boston Public Library on the grandiose theme, The Development of Religious Thought from Paganism to Christianity, approach Warhol's series in size. Warhol's recreations infuse Leonardo's familiar image, which had become a cliché, with new spiritual resonance. In these last works Warhol's technical freedom and mastery and his deepened spiritual awareness resulted in paintings which evoke what the Romantics and the Abstract Expressionists called the Sublime. His final series on the Last Supper is arguably the greatest cycle of paintings by this prolific, enigmatic and complex artist."

This late apotheosis of Warhol as a painter of profound religious murals is inevitably a surprise to casual viewers of Pop Art. They might be equally surprised to see arguments by other scholars that for 25 years Warhol had been working, theologically speaking, in the same Catholic vein. In the midst of his Pop images of food, fashion and sexually liberated "Super Stars," Warhol's intimations of sin and judgment day were never far away. His Electric Chair images and Disaster paintings are direct reminders of the closeness of heaven and hell. His Tunafish Disaster (1963) depicts several food cans with the caption "Seized Shipment. Did a leak kill." Underneath the cans are repeated photos of two women who died suddenly of food poisoning after a neighborly luncheon of tuna salad. "Warhol reminds us of the capriciousness of death; the ordinariness of the women's photographs makes the painting all the more alarming," says Zan Schuweiler Daab of Converse College, in "For Heaven's Sake: Warhol's Art as Religious Allegory."

The debate about the Catholicism in Warhol's art has actually been going on for some time. For example, biographer David Bourdon noted that the images of Jackie after John Kennedy's assassination "often make viewers feel as if they were walking along a modern-day Via Dolorosa as they relive the First Lady's agony in a new, secular version of the Stations of the Cross." (Warhol, published by Harry N. Abrams, 1989.)

Whatever the art historians now see as the moral lessons in Warhol's art, it is no surprise to his older brothers, Paul and John, that Andy was deeply religious. Growing up Byzantine Catholic in Pittsburgh, the boys were strictly raised by parents who spoke Rusyn-Slavonic, observed all the saints' days and constantly sent care packages to poor relatives in Czechoslovakia. They were taught to pray every day. For 20 years Andy made the weekly pilgrimage down the hill of South Oakland to Saline Street, in the Rusyn Valley, where St. John Chrysostom Church was located. Andy visited church regularly, but unobtrusively, in New York. Church attendance was not something, says John, that Andy would talk much about. It hardly fit his role as a high-style leader of Pop Art. He didn't even tell John that for the last four years of his life he went to a mission for the poor on Easter and Christmas to give food to the homeless.

There is a caring, accessible quality to Paul and John Warhola that has to reflect their family tradition. Soft-spoken, easy to talk to-these are traits the shy young brother obviously shared. John and Paul likewise continue their mother's tradition of sending care packages to their relatives in Czechoslavakia, seven decades after Julia first immigrated to the United States following the ravaging of Europe by World War I. On the day I interviewed Paul for a few hours at his farm near Uniontown, his wife, Ann, was taping up a large box on the truck to send to Czechoslavakia. She had gotten a good buy on quilts at Kaufmann's department store, and one by one the large boxes were going to Europe. Six decades earlier, when Paul was a boy, he used to give the pennies he made selling newspapers, or peanuts at Forbes Field, to his mother, Julia, who sent every available cent to her sisters in the Carpathian Mountains. Their father, Andrej, struggling for money, sometimes complained, but always gave in. During the 20 years Julia lived with Andy in New York, she continued to collect inexpensive clothing to send to her relatives.

Paul recalls how, when he once visited his mother's small mountain village in Mikova, the daily hardness of life in the mountains struck him. Old women, he said, gnarled and muscular from a lifetime of work, walked the solitary roads. In the fields were crude wooden crucifixes, erected by the shepherds tending sheep and cattle, so they could pray. Religion was fundamental to everyone's daily life and work.

John says that Andy had good intuitions, and once advised him to buy real estate. But as a graduate of Connelley Trade School, and for years a Sears employee, he never had the extra money to invest. Still he and his wife dressed their three sons well, and raised them to care about others. He recalls that a lady for whom his son delivered papers once came to him, when she learned who he was, to compliment him on his son's behavior. The boy had run across the street to help her home with heavy packages-it was not something that you expect from young people today. Looking after people is a kind of Warhola instinct. In his own way, Andy Warhol practiced a version of that. Homeless people would beg him for a meal, but no fool, he did not give them money, but rather told them to get a meal at a restaurant where he kept an account.

Where did Andy Warhol get his sense of intuition? How did he anticipate what would happen next in the trendy fashion scene? Both Paul and John attribute this intuitiveness to their mother. They credit her with an instinct about what would happen next-a type of "good advice" that even their neighbors respected.

Paul recalls that when Andy was shot in 1968, and was close to death-the doctors said he had a 50 percent chance of living, or dying-Julia knelt and prayed by his hospital bed. Then she told Paul not to worry-Andy would be "all right." When she herself went into the hospital a few years after her husband's death, for an operation for colon cancer, she knew she might not survive. But she assured her worried sons that she would be all right. The doctors told the boys after the operation that Julia could probably live no more than five years, but she lived nearly 30 years more.

John remembers with pride how during World War II all the young boys on the block leaving for the service stopped at the house to say goodbye to Mrs. Warhola, and that she gave them advice. She told them to "take care of themselves," and not to be reckless, not to volunteer for dangerous duty. Her realism came from the bitterness of surviving World War I in a mountain village, when the Germans burned all the houses and shot the men, and she and her sisters hid in the woods. Those memories of the war years were with her in America, and part of the lore she impressed upon her children. She told them about her own mother, who died when she heard her son, Julia's brother, was reported killed by the Germans. Then, it turned out, he was alive. He had taken off his own shredded uniform after a battle, and put on the nearly new uniform of a dead soldier, but he left his identification on the dead man. When he returned to the village later, the people were amazed-they knew he had died. Such were the family stories the Warhola boys learned from their mother.

John has a tape recording of his mother singing sad songs in her native Slavonic tongue. She seems to be accompanied by other voices-but when he asked her about that, she explained that she had taped herself, and then sang again to her own accompaniment. She did this, she said, in the expectation that someday her sons would want to hear her voice. John also remembers how Julia's way of speaking English was made to appear ridiculous in a national magazine. During an interview the reporter asked Julia questions, and quoted her imperfect grammar to make her seem foolish. Andy had asked beforehand that Julia's conversation be edited for publication-but the magazine decided to emphasize her broken English. Andy was embarrassed and upset by this manipulation of his mother. Perhaps it was one of those seminal incidents in which Andy Warhol himself learned never to be an easy mark. Instead, he became the manipulator. His mastery of calculated, innocent-sounding phrases became the quotable sign of his sophistication.

What would Andy Warhol now "say" about the decade between 1987 and 1997? The evidence of the 30 years before that suggests that whatever Andy would now say, it would be characteristically simple and understated.

Both Paul and John say Andy was always shy as a child-someone they had to look after. They agree that Andy's sophisticated reluctance to talk in public was probably still a genuine fear, however playfully disguised. When he "interviewed" the actress Farrah Fawcett for Interview magazine, John recalls that she said beforehand she was afraid of the interview-but in fact, John was convinced that Andy was more afraid than she was. They also believed, with their father, who had saved money to send Andy to college for two years before his own death in 1942, that their father's advice was correct. He predicted that somehow Andy was going to be, in the Slavonic phrase, an educated man, important, a scholar who had gone to college.

Religion, intuition, memories of war and life and death-all were part of Andy Warhol's childhood-but he never discussed them publicly. Still, theologians are now uncovering them in his art.

Had he not died so unexpectedly after an essentially routine gall bladder operation in 1987, Andy Warhol would now be 69 years old. People agree that he was very intuitive, always ahead of things, ready to perceive the next creative step as an artist. Neither Paul nor John Warhola think that he would necessarily have remained a painter. He talked about television, video, film. He had a scheme to replace himself, in interviews, with a look-alike robot, which could say things better, more satisfactorily, than he himself could say them in person. Would he have remained essentially a printmaker, a painter? That is not clear.

I asked John Warhola what, with the wisdom of old age, Andy Warhol might have been thinking about with respect to leaving some part of his wealth to benefit others. John thinks, given his own family sense of Andy's upbringing and values, that Andy would have wanted to help poor young artists, as he himself once was growing up in Pittsburgh. Clearly today the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., and the Andy Warhol Museum, have an educational mission that would have been important to Andy.

He died too unexpectedly to be fully prepared, yet his art seems to remain forever current. Vincent Fremont believes that death remained "abstract" to Andy. The art historians now see a Catholic imagination informing Warhol's sense of life and death. Andy himself, always ready to be enigmatic, once suggested that a word to carve on his own tombstone could be "Figment."