by David Lewis

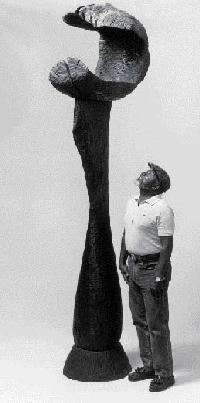

Recent sculptures by Pittsburgh artist Thaddeus Mosley are exhibited in the Museum of Art's Forum Gallery through August 3, 1997. A recent book on Mosley's work has been published jointly by the Carnegie Museum of Art and the University of Pittsburgh Press, with a narrative by David Lewis and photography by Lonnie Graham. Here are some excerpts from an interview that forms part of that book.

David Lewis: You're an African-American. Your African-Americanness permeates your life. Do you think there's an African-American "language" in art?

Thaddeus Mosley: Being African-American is something that I am. For me, as an artist, the largest contribution blacks have made to the world is African sculpture.

In the late 1940's, before I ever thought of being a sculptor, I was drawn to African art. Then I quickly grew from being interested in it to being exhilarated by the energy and inventiveness of those countless objects, made unselfconsciously by anonymous people as a part of their lives.

But you are right; I'm an African-American sculptor-not an ethnographer and not an African. As a black American I feel an affinity with African art in my blood; but it's not my only root. I'm an American also. A few years ago I was reading a poem by Stephen Crane and listening to a song by Johnny Coltrane. I made a sculpture, Trane to Crane, two different forms weaving together.

American sculptor Isamu Noguchi made a remark about sensibility being more important than status. To me it's unimportant whether an object is made by an artist of great reputation or by someone unknown. What is important is its vitality.

Sculptor Constantin Brancusi came to African art as a European, and so did Picasso. They incorporated African influences into the European traditions in which they were already working. African art became a tributary to their language.

There is Brancusi, moving in a certain direction, and he suddenly sees something in a piece of African art; it's not necessarily a new direction or a revelation, but rather a confirmation and an extension of what is already there within him.

One of my big influences was a photograph of grave markers in Georgia, which I first saw in Marshall Stearn's book, The Story of Jazz. The moment I saw that picture I thought of Brancusi's Bird in Space sculptures, and straight away I thought how the slaves who made those staves and Brancusi had never known each other existed, had never seen what each other did. Yet in each of them I saw a similar spirit, a similar approach to clean fluid shapes coming from people working close to the earth and trying to fuse the earth and human spirituality into a single form.

Brancusi was a Rumanian sculptor living and working in Paris. African art was a confirmation and an extension of a tradition he was already working in. In much the same way Brancusi and Noguchi are important to me because they confirm and extend what I do.

How do you generate your sculptural themes?

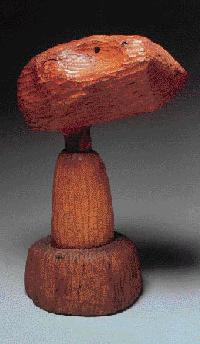

Well, first of all, I don't generate themes; my woods and stones and I generate themes together. The main woods I'm interested in are cherry, walnut and sycamore. I get them from tree surgeons or from the city's Forestry Division. I take logs that I can fit into my station wagon, so I seldom take any that are longer than six feet. Many of my sculptures are five to eight feet high and are made or two or three pieces stacked or fitted together.

A lot of my stones I pick up from sites of demolished buildings, limestones and sandstones especially. Then I explore scrapyards where I find odd pieces of metal that interest me even before I know how I'm going to incorporate them into a sculpture. I never weld such pieces or alter them. By incorporating them into a sculpture I change their context; then they come alive in a new way.

When I bring in a load of logs or blocks of stone I stack them up in my workspace. The logs are generally green and need to dry out. Every time I go to my workbench, I walk by them and get to know them better. The more I see them and re-stack them the more I see special characteristics in each one. One log may split while it's drying, another may have a scar of rot, another a twist, or a knot. Similarly, stones have different grains, colors, textures. Gradually an idea begins to assert itself, and then I start to carve.

I never made drawings. I draw with a hammer and chisel. It's a sculptural improvisation, a journey.

I channel my mental energies into a narrow sculptural focus: materials, form, rhythm, surface, relation to earth, capacity to soar. Everything I surround myself with relates to what I'm doing in my work. I listen to jazz a lot; most of what I read is non-fiction and deals in the realm of ideas. But what I'm thinking about most of the time is sculpture. My basic approach hasn't changed in years. In every sculpture there are new explorations. That's what makes sculpture alive and keeps me sculpting.

Several of your sculptures appear to include sexual images.

I've never set out to make sexual images any more than I might attempt to consciously impose any other sort of representation. If we speak of growth, thrust into space, concavities, rounded masses and so forth we're bound to run into sexual images. Nature is full of them, whether in fruits, flowers, trees, rocks or clouds. So are sculptures.

The ripple of chisel marks is important to me. You might say they are related to my interest in jazz and dance. I use different widths and depths of gouge to make different marks. Shadows are the means by which one can appreciate the rhythms of chisel marks. The broad deep gouges hold a depth of shadow and the narrow shallow ones play along the surface of forms.

Sometimes I combine other materials with wood or stone-bolts, nuts, steel cable, plastic, wire, cloth or bits of machinery. There's nothing new in this; just look at African or American Indian art. You have to listen to the sculpture while you are working on it. It will tell you what it needs.