Andy Warhol's Influence in Japan

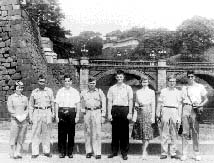

Above: Warhol

takes a sightseeing tour of Tokyo in 1956 on the Pigeon Bus Company, Limited. Warhol

is second from right; his friend Charles Lisanky is at far right.

Archives of the The Andy Warhol Museum.

Chances

for first-hand contact with Warhol's paintings and film in Japan are limited. Warhol

himself came to Japan only twice, on his world trip as a young commercial artist in

1956, and in 1974 for a solo exhibition that introduced his works to the Japanese

audience. But his works and his amorphous reputation in Japan have become, through

media manipulation, a complete topic for popular discussion, and any kind of argument

about Warhol has become possible in Japan.

Today most articles and essays

reflecting the increasing Warhol presence in Japan are about the artist's mysterious

charm. Many writers deal with Warholian anecdotes, or are consumed with conceptual,

enlightened arguments regarding him. Warhol's comments, which can be interpreted many

ways, are quoted.

In contrast, there are few concrete essays on Warhol's works,

or on Warhol's place in American culture and art. In the art world at large, a discussion

is underway on Warhol's contemporaneity and work overlapping with that of artists

such as Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, and the technique of color field

painting and minimal art. But in Japan, the maxim "minimalism follows pop"

precludes any attention being paid to the relationship between the two styles.

There

has been continual simplification of the periods in Warhol's work, as if Warhol had

been transformed overnight from commercial artist to pop artist, taking the murder

attempt by Valerie Solanas as an opportunity to increase his business as an artist.

There is little sense in Japan of one period penetrating the other.

I

think it is important at least once to set aside Warhol's charm, and take in the works

themselves. In reexamining the relationship between Warhol the person and the works,

new possibilities for the Warhol image emerge.

However, the acceptance of Warhol

in Japan has not been based on the pure illusion of fictional images piled one upon

the other. If Warhol were simply a mirror in Japan, the reflected image would accurately

reflect our wants and be one aspect of what Warhol achieved.

In discussing

Warhol's relation to Japan, the first thing to emerge is the overwhelming abundance

of American images in postwar Japan. Whether seductive or repellent, the United States

has had an overwhelming presence in Japan for half a century.

Japanese people

were attracted to the opulent American lifestyle they saw for years on television

and in magazines. The Japanese of the late 1960s and early '70s had a strong desire

for economic growth, partly fueled by their exposure to American images, and to them

Warhol's 1960s paintings coolly reproduced the good and the bad in the United States,

and his underground film and music reflected both American prosperity and failures.

Then in the early 1980s, when Japanese society shifted from production to

circulation and consumption, from objects to information, Warhol also resurfaced as

a symbol of New York consumerist culture and post-modernity. Through Warhol, the Japanese

envisioned America-particularly New York-as the cultural center.

The two periods

when Japanese interest in Warhol peaked were the times when the boundary between high

art and subculture was blurred in Japan and the United States, and Warhol was a symbol

of these historic moments. In Japan, Warhol was acclaimed as a ground-breaking artist

who crossed set boundaries. The fact that Warhol did not start out as a fine artist,

but rather as a graphic artist, made him more amenable to Japanese people.

Furthermore,

anti-modern qualities illustrated during Warhol's lifetime aroused the empathy of

the Japanese people. These anti-modern qualities included his rejection of the separation

between art and life, the blending of high art and subculture, the possession of a

subjectivity based on renunciation of a consistent identity, and the practice of group

production through the division of labor and collaboration.

These Warholian

issues are universal key points in understanding late-20th-century modern art. The

Japanese must also remember, however, that Warhol developed his art and life in the

particular system of the United States; we cannot fantasize about America through

Warhol forever. Now is the time to comprehend from a Japanese perspective Warhol,

the greatest aporia since Duchamp, in readying a different response to modern art.

Akio

Obigane, curator in the Cultural Projects Department of Asahi Shimbun in Tokyo, is

a co-organizer of the exhibition Andy Warhol 1956-1986: Mirror of His Time, which

is currently travelling to three Japanese museums. This article is adapted from an

essay by Obigane in the exhibition catalogue.