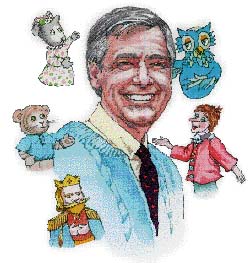

IN FRED WE TRUST

by Sally Kalson

Who else but Fred Rogers would be the subject of a book-length tribute that begins with three pages of denunciation? Hysterically funny denunciation, yes; denunciation that turns out to be a kind of revival-tent device, emphasizing the writer's sins in order to dramatize his conversion; but dununciation nonetheless.

No one I can think of. But then, no one except Fred Rogers has spent the last quarter-century speaking so slowly, gently, honestly and yes, fearlessly to the inner-most concerns of small children.

Only Mister Rogers' low-wattage persona, his direct simplicity, his utter lack of guile or self-parody could inspire the kind of hilarious essay that Bob Garfield wrote as the forward to Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Children, Television and Fred Rogers, published this spring by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

The book is worth reading for Garfield's essay alone, because it so neatly sums up everything that's wrong with out culture's distortions of childhood and, by contrast, everything that's right about Fred Rogers' work.

It is to the credit of editors Mark Collins and Margaret Mary Kimmel that they used this piece as the book's forward, in essence leading with their left. Because a lot of what follows is very serious indeed. At times it's almost reverential, although not inappropriately so, given the fact that no one else in television has done as much to reassure children of their special place in the world

Yet it would have been disingenuous to ignore the perverse reaction that such stunningly straightforward sincerity brings out in so many cynical adults-who, for some bizarre reason, seem to think Fred Rogers should be playing to their jaded sensibilities instead of to their children's innocent ones. And by beginning the book as they do, the editors disarm the naysayers before they have time to get off the first misguided shot.

The forward is not the only reason to read the book. The 13 original essays that follow, each analyzing a different aspect of Rogers' work, go a long way toward explaining why his nonsectarian TV ministry to children has endured for so long.

Pittsburgh-based writer Jeanne Marie Laskas, who has done so many articles on Rogers over the years that she must surely have earned a Ph.D. in Fredness by now, reveals the man behind the TV screen to be exactly the same as the man inside the TV screen, only more so.

Long-time WQED producer Mary Rawson offers a surprising glimpse of Rogers' devoted fans at the other end of the age spectrum-the older adults who drink in his message of respect and acceptance as thirstily as do their grandchildren.

Other essays cover Mister Rogers' use of make-believe; its theology; its messages to parents; its music (via an interview by Eugenia Zuckerman with Yo-Yo Ma); its puppetry.

Child psychologist Nancy Curry, who trained with Rogers under child-development specialist Margaret McFarland, explains Rogers' use of make-believe as a gateway to a child's reality. Paula Lawrence Wehmiller explores his contributions to the teaching of tolerance. Marian Wright Edelman's afterword describes why "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" has never been needed more than it is right now.

Moving through these writings, you cannot help but realize the depth of knowledge and understanding of children and child development that lie beneath the deceptively simple sets of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood."

And if you grew up watching television in Pittsburgh as I did, you can't help but feel a personal connection to Fred Rogers and his work.

I should note here that "The Children's Corner" with Fred Rogers and Josie Carey was not high on my childhood viewing list. By the time I discovered it on the fledgeling WQED, my heart already belonged to Hopalong Cassidy, Johnny Mack Brown, Annie Oakley and Lash LaRue. I was absorbed in their clear-cut images of good and bad, their thrilling chases on horseback, and, in the case of Lash, that bullwhip that was as much a threat to evil as any six-shooter. The simple puppets and gentle voices never really had much chance of being heard among the bang-bang, shoot-'em-up that marked my fantasy life.

So it was not as a child that I came to sit in one of Mister Rogers' television pews. It was-and is-as a mother. As a mother, I have come to appreciate the special genius of Fred Rogers far more than I ever, as a child, appreciated the whipmanship of Lash LaRue.

As a mother, I am raising a child in a world where the bang-bang shoot-'em-up is not fun fantasy, but appalling reality. And in that context, it's hard to find a safe haven for children today that will still be safe tomorrow. That's the role that "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" fulfills.

I trust Fred Rogers with my daughter, and she loves to "be" with him. We both know he will reassure her, speak kindly to her, tell her that lots of kids are afraid of clowns or big dogs, and that it's okay to have those feelings. We trust him to lead her throuugh an orange juice factory asking all the questions she would ask. I even trust him as a music teacher. It was, after all, because of a "Mister Rogers" episode that she pointed weeks later to a cellist on TV and, at the age of two, said: "Yo-Yo Ma."

I trust Fred Rogers never to belittle her, or scare her, or confuse her. And in the current TV market, that's saying a lot.

As a mother, I abhor the crazed, frenetic children's TV that whittles kids' attention spans to a nano-second; the trafficking in sexist and violent images that desensitize children in the name of ratings and profits; the view of children as little consumers who, once stoked with enough desire for some toy or cereal, will nag their parents until they get it.

A friend would never do that to your child. A friend would tell your child what Fred Rogers tells mine all the time: It's her he likes. It's not the things she wears (light-up sneakers with Sesame Street characters not required). It's not the way she does her hair (even if she did cut off a whole handful above the ear as an experiment). But it's her he likes.

You'll hear that voice again and again in this book, but only as conveyed by other people. Rogers himself was not asked to contribute an essay. That, says editor Kimmel, was intentional. "Our purpose was to publish a thouughtful analysis of his contribution," she said. "We wanted it to be about his work, not about him."

In the end, however, it's clear that the two cannot be separated. "Mister Rogers Neighborhood" could only have been produced by Fred Rogers. And this book, while not technically conceived as a testimonial, inevitably had to become one.

One of the shots in Lynn Johnson's closing photo essay shows why. It depicts a young woman at her college commencement, dressed in cap and gown and triumphantly holding aloft a Daniel Striped Tiger puppet.

Mister Rogers has kept faith with America's children, and America's children have kept faith with him.

Sally Kalson is a journalist who writes a weekly column for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.