Christopher Wool:

Painting about Painting

Christopher Wool:

Painting about PaintingThe first major survey of Wool’s work, which was organized by the Museum

of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and opens at Carnegie Museum of Art

on November 21, includes approximately 50 works ranging from the time of

Grynsztejn’s visit to the present. The pieces in the exhibition, which

are drawn from American and European collections, include patterned, stamped,

and silkscreened paintings and works on paper. Also included are Wool’s

stenciled text paintings, of which the Carnegie Museum of Art owns the

largest example.

At the time of Grynsztejn’s first studio visit, Wool was working in

black and white, producing tightly controlled drip paintings, and running

decorative rollers over a white ground to produce floral and gate-like

images. Soon after seeing the words sex and luv written in black paint

on the side of a white truck outside his studio, Wool stenciled sex and

luv in black repeatedly across a white ground. His second text painting,

Apocalypse Now, recasts a letter from the Francis Ford Coppola film that

says: sell the house, sell the car, sell the kids. The message evokes a

vision: no house, no family, none of those accoutrements that make ordinary

life worthwhile. Wool did not simply stencil the words—he broke them up

so that reading the text in the usual way is an effort. You can’t scan

it, you have to decipher it.

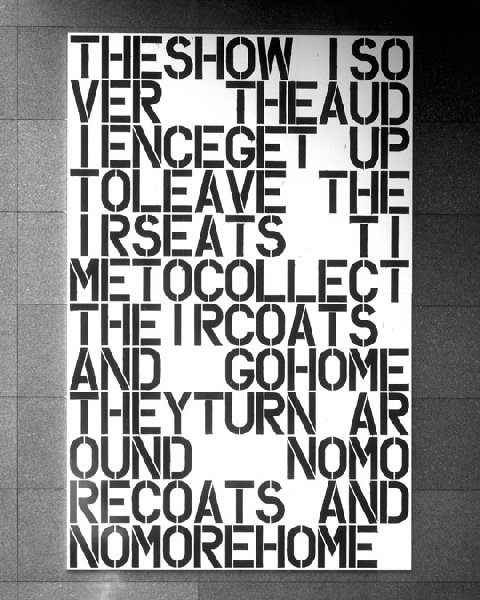

The untitled text painting that was included in the 1991 Carnegie International is based on a proposal submitted to exhibition curators Lynne Cooke and Mark Francis, formerly chief curator at The Andy Warhol Museum. It was exhibited during the International outside the museum next to the Sculpture Court, and now hangs in the museum’s rear entrance.

The statement in the painting is lifted from Greil Marcus’ social commentary, Lipstick Traces, and is a definition of nihilism as quoted by situationist Raoul Vaneigem: The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats. Time to collect their coats and go home. They turn around. No more coats and no more home.

“It’s not just a statement,” Francis cautions. “It’s a painting.” Wool’s

earlier work, wrote the late John Caldwell, a former curator of contemporary

art at Carnegie Museum of Art, to whom the exhibition is dedicated, was

about “the process of painting itself.” According to exhibition curator

Ann Goldstein, Wool still returns today to the question of how to paint,

rather than what.

In the large text paintings, a viewer can see the drips, the unevenness

of the letters, can regard it as a pattern of black on white rather than

a written message. As Grynsztejn points out in her catalogue essay,

“Unfinished Business,” “inherent in any viewer’s reception is the experiential

fact of reading and looking as simultaneously exclusive acts.... Wool deliberately

choreographs a collision between different components of language—grammatical,

semantic, visual, imaginary, and spoken—that conveys an emotional magnitude

beyond the range of everyday speech and closer in spirit to the true proportions

of Wool’s subject: the inherent inefficacy and near-constant failure of

language.” The text paintings, according to Grynsztejn, call up the psychic

territory of the streets of New York, the urban turbulence that takes place

outside of Wool’s studio.

Wool’s newer work, incorporating proofreader’s marks, x’s and o’s, undulating lines, “veers toward image,” Grynsztejn writes, “approaches language, and devolves into shape again in a purposeful fluctuation that steadfastly refuses resolution.” This work, like the text paintings, tempts the viewer to “read” it, but ultimately resists. As in all of Wool’s work, it is the process, the physical properties of the paint, that a viewer ultimately returns to. As critic John Lewis writes in the August 1998 Harper’s Bazaar, Wool is “one of the very few artists keeping painting alive, aware, ornery and unafraid.”

Ellen S. Wilson is a contributing editor to Carnegie Magazine.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |