The first question about the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Manchester is, "Where is it?" In fact many people do see part of it - as they speed out of the city on Ohio River Boulevard, or 65 North. Twenty blocks of old houses appear on the right as drivers pass by on the elevated expressway high above the grid of the neighborhood streets. These are the houses at the western edge of Manchester, which extends another five blocks away from the river, until it meets the North Side at Allegheny Avenue.

Manchester is one of Pittsburgh's oldest neighborhoods, and the current display about it at The Heinz Architectural Center is called by curator Dennis McFadden a "project" and not an exhibition. He says that The Heinz Architectural Center wants to encourage people to see and react to their environment in different ways.

The Manchester sketchbook is wide open to many points of view, and includes the comments of residents, and "sound portraits" of Manchester by Michael Pestel's Sound Design class at Chatham College - the sounds of moving trains, children's voices in the playground, birds, and singing in the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Easter Sunday. Pulitzer-prizewinning photojournalist Martha Rial of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has made portraits of new and old residents. The Manchester Craftsman's Guild will display photographs taken by young people in its photography classes. A video installation by Andres Tapia-Urzua reveals interior aspects of the neighborhood from which residents look at the rest of the city.

"The whole point is to emphasize multiple views of architecture," says the project coordinator, architect Paul Rosenblatt of Damianos + Anthony PC. "This is not a single message exhibition. It is presumptuous to superimpose the +objective' view of professional architects here. We need a balanced view."

Rosenblatt argues that people should value their own neighborhoods more personally, and that the intimacy of their daily routine is actually the best defining feature of any neighborhood. For some people the experience includes history. A vacant lot where a family house once stood always colors the meaning of the street for some residents. Distinguished architecture may be irrelevant to everyday life, and there can be an architecturally modest place - such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church - which is an important religious sanctuary and a vibrant center of community life.

McFadden and Rosenblatt like the metaphor of the sketchbook. You can carry it around all the time, add your random, private thoughts to it, catalogue those special things that appeal to you alone, and never feel the need for a formal presentation. The Manchester sketchbook is like that.

But why Manchester? Why this one community to lead off what The Heinz Architectural Center hopes to produce in the future as a series on Pittsburgh itself - a city known for its diverse and strong ethnic neighborhoods?

The complexity of Manchester has important lessons to teach about 20th-century urban life, especially in Pittsburgh. Manchester is a typical example of the results of American urban policies - in social engineering, architectural problem-solving, and in government and preservation politics. When the community began to rebound from decades of neglect in the 1980s, the contemporary Manchester solutions to urban blight became examples for other cities to study, and eventually a national program was developed on the Manchester model.

Manchester was founded in 1832 and named after a British industrial city in the center of England. A working-class river community with access to the Ohio, Manchester grew through manufacturing in the last century. Business and industry developed along the river, and the houses were several blocks further inland. By the early 20th century block after block of late Victorian houses were lavish evidence of the prospering middle class.

Then decisions about transportation and local politics began to change it. The expanding railroad tracks (now the Conrail tracks) increasingly defined the edge of the residential area to the north, and in the 1960s the expressway along Chateau Street became a high wall between the homes and the riverfront. The colossal highway projects of the era cut through many neighborhoods in Pittsburgh.

Manchester was annexed by Allegheny City in the 19th century, and in the early 20th century Allegheny City was annexed by Pittsburgh - making Manchester the Ohio River edge of the city's North Side. Social engineering also took its toll. When construction of the Civic Arena on the lower Hill District caused resettlement of thousands of African-American Pittsburghers, many moved to Manchester. It became an increasingly black community, walled off from the riverfront and without a central business or shopping corridor. It became isolated and identified with urban poverty, and the stately old Victorian houses fell into decay. New zoning codes promoted the demolition of the old Victorian houses in favor of modern suburban-style houses in the middle of the city.

Then, in Pittsburgh fashion, signs of a renaissance appeared. Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation made a commitment to preserve the architectural heritage of Liverpool Street, and creative partnerships with city agencies began to pay off. The Manchester Craftsman's Guild brought a new center of the arts and education to the area. In 1982, tired of destroying beautiful old houses in order to construct more expensive smaller ones, the city under Mayor Richard Caliguiri promoted the Great House Sale, which allowed people to buy old buildings in Manchester for as little as $500. The Manchester Citizens Corporation broke new ground for developers and homeowners in arranging for low-interest loans for restoration rather than demolition. An approved list of contractors began to rebuild and restore the housing stock, and local pride grew in preserving the architectural heritage. Architects tried new things, such as erecting a row of houses that depended upon solar power.

Manchester became the basis for a nationwide model of urban renewal planning. A sketchbook of daily life in Manchester today offers a lot for city dwellers to contemplate.

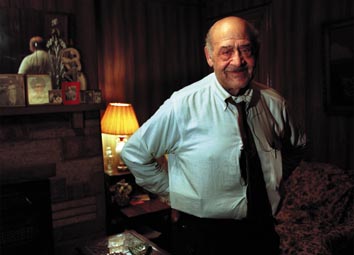

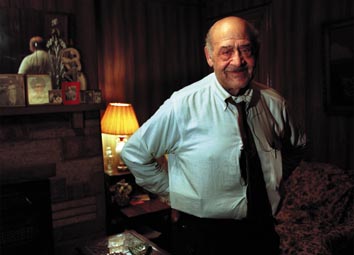

Doris Carson Williams, director of Museum Special Services at Carnegie Museums, has her own personal sketchbook of impressions about Manchester. She and her husband moved there following the Great House Sale, and have been pleased with the neighborhood for many reasons. They restored their house. She likes the central location, which gets her downtown, to Oakland or to the airport conveniently. She can be in the Strip District to shop for food in six minutes. The small stores on the corners and at the fringes of the neighborhood serve most daily needs. And she likes the diversity of people, from young professionals, to middle managers, entrepreneurs, and senior citizens - African American as well as white.

Like most patriots, she knows her civic boundaries and local traditions. She points out that Manchester is not the Central North Side, which begins at Allegheny Avenue, and that there is no Section 8 housing in Manchester. She notes that new construction requires off-street parking, and that one reason passers-by see only abandoned houses is that the new homeowners want to face the quiet streets, and build out of sight of the expressway.

She loves the brick streets of Manchester, and the beauty of the seasons in the picturesque streetscapes. She likes the thriving churches, and the park behind Manchester School. She is proud of Manchester. "It's really beautiful. It will be incredible when it's done," she says. But of course a neighborhood is never "done," since in a vibrant neighborhood civic dreams and architectural plans are never fulfilled, and always in a process of change. That is why the first neighborhood exploration by The Heinz Architectural Center is a complex sketchbook of neighborhood realities, both physical and personal, and is not a professional plan or historic survey.

- R. Jay Gangewere

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |