Mariko Mori is a 31-year-old artist, a former fashion model and student of fashion design, who was born in Japan and lives in Tokyo and New York. Thomas Sokolowski, director of The Andy Warhol Museum, called her "a cross between a geisha girl and Gidget," and she has also been described as a cyberchick and as Barbarella. With her eye-popping, oversized, computer-manipulated images starring herself in various guises, she is getting a lot of attention in the art world. Who is she really? What is she doing at the Warhol? And what are the connections between her and everybody's favorite surrealist, Salvador Dali, also showing at the Warhol Museum?

Mark Francis, chief curator at The Andy Warhol Museum, and Margery King, associate curator, discussed these issues and more with Carnegie Magazine contributing editor Ellen Wilson.

Wilson: Mariko Mori once told an interviewer that she was a child of Andy Warhol and a grandchild of Duchamp. "It was consumerism," she said, "that created kitsch." What does she mean by kitsch in this context?

King: I asked Mori that question. For her, kitsch is different from Pop, both in taste and sophistication. Kitsch is cuter, less savvy; Pop has a self-awareness about it. Pop looks at culture and represents it in a very knowing way, whereas kitsch is more sentimental.

Francis: Historically, at a certain point there was a complete gap between the avant-garde and kitsch. You had to be one or the other. Now, principally because of Warhol, it is harder to make those distinctions between kitsch and art. Artists don't start out trying to make kitsch. Mariko Mori is not actually making kitsch, she is playing with the idea of kitsch as you see it in popular culture.

King: It has been wonderful to discover, in working at the Warhol museum, how many, many artists feel that Warhol made it possible for them to do the work they are doing. While we do of course show his work here, we also look at what else is out there that reflects back on Warhol's work and allows us to put it in context, the "big" context of art.

Wilson: Was Dali also one of those artists who paved the way for Mori to do what she is doing now?

Francis: Yes, I think so. She may say Duchamp because he is more respectable as a precursor, more austere and intellectual, but Duchamp and Dali together are two key figures prior to Warhol who were interested in the same things. All these artists share a persona that went beyond the paintings, films and other artworks that they actually made, and that served as kind of a front. Mori also has a persona that is reflected in what she makes. She is outrageous and provocative, like Dali. Dali had this bad-boy quality that was a part of the way he promoted himself to the world.

King: And while Mori and other artists feel a tremendous debt to Warhol, they go beyond what Warhol did. So Mori creates many different personas, which she sees as complete fabrications. She is only the model, and as a former model herself she has a very sophisticated understanding of how the commercial world uses models to get messages across.

Francis: Young artists today do see their connection to what they are doing differently. I don't think the idea of the avant-garde in reaction to popular culture applies at all anymore. These artists would much rather see themselves as a part of, or sub-part of, popular culture. The ways in which artists connect with Hollywood, or fashion, those over-arching, spectacular cultures, is different. They want to be a part of it, they're not frightened of it in a way in which artists in some other generations would have been.

Wilson: They don't have disdain for it.

Francis: Exactly, and one of the most interesting things about Warhol and Dali in this context is that they wanted to operate in those worlds, too. Dali had projects with Alfred Hitchcock and Walt Disney. So when people come to the museum, they can see different ways in which artists make connections with popular culture. In this instance, I think popular culture connects very closely with subconscious desires and dream life, the wacky, wild side of things, not just sensational front-page popular culture.

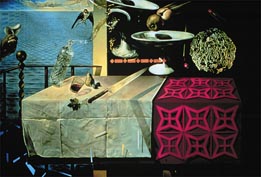

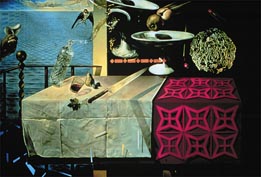

King: Yes, and while a lot of Mori's work is easily identifiable as pop, her newer work seems to reflect the life of the mind. She's not leaving behind pop as represented by Warhol, but she's trying to link that with an internal life that might be represented by an artist like Dali. She's trying to find the balance between those things. The piece that is most emblematic of her early works would be Birth of a Star, where she casts herself as a teen rocker in a sequined skirt with spiky purple hair in a computer-manipulated environment. Her more recent work explores eastern philosophy but she's using the same techniques, she's casting herself in roles and in settings that suggest a more transcendental experience.

Wilson: One critic said she creates "images of male fantasy from a woman's point of view."

King: I would say that in all of her work, she's using the techniques that make advertising so successful. Perhaps that does have to do with male fantasy, but she is using that vocabulary to express her ideas. One example would be Tea Ceremony, where she casts herself as a Japanese office girl serving tea on the street to a male office worker. She's certainly suggesting that we need to think about this relationship.

Francis: There are still questions in Japan about whether you can be a traditional Japanese woman in a kimono or a contemporary Japanese woman in Issey Miyake. You can't be both simultaneously. She's working off that in a way that may be critical.

King: And while Japan is a traditional culture, it has also embraced technology and a global point of view.

Wilson: Mori herself does not see technology as an evil force but as a force for good.

King: Absolutely. And she realizes it's the way we're going.

Francis: You don't think its ambivalent?

King: I think she sees that there has been a loss of balance, and that is what is motivating her newer work.

Wilson: Is it simplistic to say that she has created a bridge between Warhol and Dali?

Francis: There are signs in their work, images and objects, like the reflective eyeballs in one of Mori's photos. You look at the overall image and realize there is something weird or disturbing. That is one of the great contributions of Dali, visualizing those disturbing or repressed images and making them part of everybody's landscape. He turned things which are unusual into images that make you think, that's like last night's weird dream. That is the great trick for artists, finding images that go beyond their own personal circumstances into something which people can connect with. These artists we've been talking about do that in very different ways, and you could hardly find three people from more dissimilar backgrounds - working class Pittsburgh, affluent Tokyo, and pre-war Catalonia. Artists make the unique into something that connects with everybody's life in the end, rather than just drawing on common culture.

King: We hope people will look at these exhibitions and come to their own conclusions. We've been talking about the paths between these three artists, but there are a lot of paths that can be taken. The context of the Warhol museum gives us a powerful place to start.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |