You didn't flush it down the toilet, did you?" my son asks, gazing at me severely as I emerge from the bathroom after disposing of a particularly gruesome spider. "Was he dead?"

"Um, yes," I say, certain that by now "he" is. My five-year-old son likes bugs, especially spiders. ("Arachnid, Mommy. Cephalothorax. Do you know what cephalothorax means, Mommy?") "It's okay," I say. "It wasn't a nice bug."

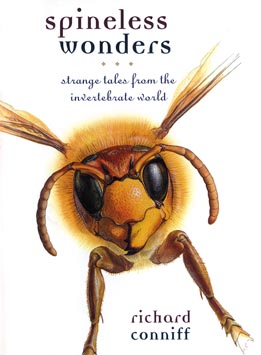

Of course distinguishing between nice and bad bugs is against one of my basic principles of childrearing ("How can you tell who's a bad guy?" I frequently ask my son and his friends.) But bugs - I just don't much like them, that's all. And after reading Richard Coniff's bizarrely compelling book Spineless Wonders, while I appreciate the complexity of their lives, civilizations, and various odd behaviors, I still won't hesitate to flush away any flies, spiders, or rolling potato bugs that have the temerity to enter "my" house. I suspect Conniff would think that's okay. While he appreciates the beauty and purpose of dragonflies, moths, earthworms and leeches, he is never sentimental about their impact on humans. And besides, there are zillions of the little pests.

Richard Conniff is a journalist who came to his appreciation for entomology a bit late in his career. His work for various nature magazines like Smithsonian and National Geographic allows him to tag along on scientific expeditions in a way not unlike some of the subjects under study, who depend on other creatures for sustenance (fleas), transportation (sloth moth) or other basic necessities. The volume into which his articles are collected, and recently released in paperback, sets out "to celebrate the strangeness and wonder of both the invertebrate world and its attendant humans."

He succeeds. The book is filled with fascinating bits about the little beasts that so often seem to be under foot. In fact, invertebrates, he tells us right away, represent more than 99.5 percent of all animal species. "A spaceship visiting the blue planet would take them, not us, as the typical earthlings."

Conniff has a wide-ranging, easy style. He is able to detail reproductive practices in flies and tarantulas with aplomb in one section and ponder evolution or other weighty matters in the next. On his newfound appreciation for dragonflies, who predate dinosaurs: "I love catching them to hold in my hand for a few moments. The eyes are misty and deep, like a fortune-teller's ball. Colors flash across them. Black patches like pupils seem to stare back, as if considering who I am and where I stand in the history of the planet. Looking into those eyes is like looking back in time."

One of the more heartfelt chapters, "A Small Point of Interest," goes head to head with mosquitoes. As in so many of the essays, there is some description of the fieldwork necessary to study these creatures, and here we have a graphic description of just how unpleasant it is to be hot, sweaty, and plagued by blood-sucking insects in the rain forest. But things could be worse. "In the Arctic tundra, for instance, you could get frozen and sucked dry at the same time. The spring snow melt hatches all the dormant mosquito eggs at the same time. . . . Canadian researchers once sat still in such a swarm long enough to report that they suffered nine thousand bites a minute, a rate sufficient, at least in theory, to drain half their blood supply in two hours."

While Conniff appreciates some mosquito skills - such as flying through the rain and dodging the drops to arrive at their destination dry - they are one of the few species that, along with slime eels, he seems to genuinely dislike. Mosquito-borne illness is a real threat, and he recounts incidents of calves being sucked to death on the Louisiana coast in 1963, a yellow fever epidemic in Peru in 1995, outbreaks of dengue fever in southern Texas, and other horrors.

By contrast, the lovely and harmless moth, though legion, is poetry on wings - or almost. Although there are more moth species than all mammals, birds, fish and reptiles combined, moths, in contrast to their butterfly cousins, have unfairly gotten bad press. Nobody deliberately plants moth gardens, for example. But moths are important pollinators, silk producers, and food sources. They can be beautiful. Different moth species have elaborate adaptations to single plants, changing with the seasons not only in appearance but in body chemistry as well. He may not invite them into his sweater drawer, but unlike the mosquitoes battling to enter his room on a summer night and suck his blood, Conniff seems more than tolerant of the moths who rule his back yard.

This book is full of good stories and bizarre little facts (How, exactly, do houseflies spend their time? And did you know that Charles Darwin played the piano for his earthworms? All in the guise of scientific inquiry.) While you may not want to read it at lunch, you don't have to like bugs at all to enjoy Richard Conniff's exposÄ of our fellow earthlings.

Ellen S. Wilson is a contributing editor of Carnegie Magazine.

Contents |

Highlights |

Calendar |

Back Issues |

Museums |